1 min read

VIDEO: Stalin Biographer Geoffrey Roberts Exposes Ukraine-War Lies

Dr. Roberts is one of the critical western historians who also dares to speak his mind when it comes the War in Ukraine…

9 mins read

VLADIMIR PUTIN, Russia’s president, was cock-a-hoop on October 22nd when he welcomed world leaders including Narendra Modi of India and Xi Jinping of China at the BRICS summit in Kazan on the Volga river. Last year, when the bloc met in South Africa and expanded from five to ten members, Mr Putin had to stay home to avoid being arrested on a warrant issued by the International Criminal Court in The Hague. This time he played host to a rapidly growing club that is challenging the dominance of the Western-led order.

Now in their 15th year together, the original BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have achieved little. Yet Mr Putin hopes to give the bloc heft by getting it to build a new international payments system to attack America’s dominance of global finance and shield Russia and its pals from sanctions. “Everyone understands that anyone may face US or other Western sanctions,” Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, said last month. A BRICS payments system would allow “economic operations without being dependent on those that decided to weaponise the dollar and the euro”. This system, which Russia calls “BRICS Bridge”, is intended to be built within a year and would let countries conduct cross-border settlement using digital platforms run by their central banks. Controversially, it may borrow concepts from a different project called mBridge, part-run by a bastion of the Western-led order, the Swiss-based Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The talks will shine a light on the race to remake the world’s financial plumbing. China has long bet that payments technology—not a creditors’ rebellion or armed conflict—will reduce the power that America gets from being at the centre of global finance. The BRICS plan could make transactions cheaper and faster. Those benefits may be enough to entice emerging economies. In a sign that the scheme has genuine potential, Western officials are wary that it may be designed to evade sanctions. Some are frustrated by the unintended role of the BIS, known as the central bank for central banks.

America’s dominance of the global financial system, centred on the dollar, has been a mainstay of the post-war order and has put American banks at the centre of international payments. Sending money around the world is a bit like taking a long-haul flight; if two airports are not linked, passengers need to change flights, ideally at a busy hub. In the world of international payments, the biggest hub is America.

The centrality of the dollar provides what Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman, two scholars, call “panopticon” and “choke-point” effects. Because almost all banks transacting in dollars have to do so through a correspondent bank in America, it is able to monitor flows for signs of terrorist-financing and sanctions-evasion. That provides America’s leaders with an enormous lever of power.

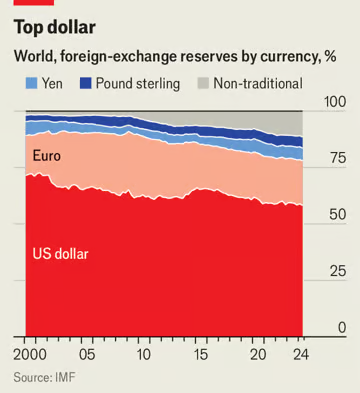

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the West froze $282bn of Russian assets held abroad and disconnected Russian banks from SWIFT, which is used by some 11,000 banks for cross-border payments. America has also threatened “secondary sanctions” on banks in other countries that support Russia’s war effort. This tsunami has prompted central banks to accumulate gold and America’s adversaries to move away from using the dollar for payments, which China views as one of its biggest vulnerabilities.

Mr Putin is hoping to capitalise on this dollar dissatisfaction at the BRICS summit. For him, creating a new scheme is an urgent practical priority as well as a geopolitical strategy. Russia’s foreign-exchange markets now almost exclusively trade yuan, but because it cannot get enough of this currency to pay for all of its imports, it has been reduced to bartering.

Mr Putin wants the summit to advance plans for BRICS Bridge, a payments system that would use digital money issued by central banks and backed by fiat currencies. This would place central banks, not correspondent banks with access to the dollar clearing system in America, in the middle of cross-border transactions. The biggest advantage for him is that no one country could impose sanctions on another. Chinese state media say that the new BRICS plan “is likely to draw on the lessons learned” from mBridge, an experimental payments platform developed by the BIS alongside the central banks of China, Hong Kong, Thailand and the United Arab Emirates (see chart).

That BIS experiment was innocent in design and initiated in 2019, before Russia’s full-scale invasion. It has been stunningly successful, according to several people involved in the project. It could cut transaction times from days to seconds and transaction costs to almost nothing. In June the BIS said mBridge had reached “minimum viable product stage” and Saudi Arabia’s central bank joined as a fifth partner in the scheme. This week an Emirati official said the platform has since processed hundreds of transactions worth billions of dollars in total—a figure that is growing rapidly. By creating a system that could be more efficient than the current one—and which would weaken the dominance of the dollar—the BIS has unwittingly stepped into a geopolitical minefield.

“If someone is transacting outside of the dollar system for political reasons, you want that to be more expensive for them than the dollar system,” says Jay Shambaugh, a Treasury Department official. The efficiency gains of new kinds of digital money may erode the use of the dollar in cross-border trade, according to the Fed. Reciprocally they could boost China’s currency. Speaking to bankers and officials about mBridge in September, a Hong Kong official said it “provides another opportunity to allow the easier use of the renminbi in cross-border payment, and Hong Kong as an offshore hub stands to benefit”.

Is it possible that mBridge’s concepts and code might be replicated by the BRICS, China or Russia? The BIS doubtless views mBridge as a joint project and believes that it has the ultimate say over who can join. Yet some Western officials say that participants in the mBridge trial may be able to pass on the intellectual capital it involves to others, including participants in the BRICS Bridge. According to multiple sources, China has taken a lead on the software and code behind the mBridge project. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank, leads its technology subcommittee and, according to comments made by a BIS official in 2023, its digital ledger “was built by” the PBOC. Perhaps this technology and know-how could be used to build a parallel system beyond the reach of the BIS or its Western members. The BIS has declined to comment on any similarities between its experiment and Mr Putin’s plan.

The BRICS’s foray into the payments race reveals the new geopolitical challenges facing multilateral organisations. At a meeting of the G20 group of large economies in 2020, the BIS was given the job of both improving the existing system and, at China’s urging, of experimenting with digital currencies. Earlier this year Agustín Carstens, its boss, called for “entirely new architectures” and a “fundamental rethink of the financial system”. As different members of the organisation have rival objectives, staying above the fray is getting harder. The world has become more difficult to navigate, acknowledges Cecilia Skingsley, the boss of the BIS Innovation Hub. But she says the BIS still has a role to play in solving problems for all countries “almost independent of what other kind of agenda they might have”.

One option for America and its allies is to try to hobble new payments systems that compete with the dollar. Western officials have warned the BIS that the project could be misused by countries with malign motives. The BIS has since slowed down its work on mBridge, according to some former staff and advisers, and is unlikely to admit any new members to the project.

Another option is to improve the dollar-based system so that it is as efficient as new rivals. In April the New York Fed joined six other central banks in a BIS project aimed at making the existing system faster and cheaper. The Federal Reserve may also link its domestic instant-payments system with those in other countries. SWIFT plans to conduct trials of digital transactions next year, leveraging some of its incumbent advantages including strong network effects and trust, says Tom Zschach, its innovation chief.

Any rival BRICS payments system will still face huge challenges. Guaranteeing liquidity will be difficult or require large implicit government subsidies. If the underlying flows of capital and trade between two countries are imbalanced, which they usually are, they will have to accumulate assets or liabilities in each other’s currencies, which may be unappealing. And to scale up a digital-currency system, countries must agree on complex rules to govern settlement and financial crime. Such unanimity is unlikely to win the day in Kazan.

For all that, the BRICS scheme may have momentum. There is a broad consensus that current cross-border payments are too slow and expensive. Although rich countries tend to focus on making it quicker, many others want to overturn the current system entirely. At least 134 central banks are experimenting with digital money, mostly for domestic purposes, reckons the Atlantic Council, a think-tank in Washington. The number working on such currencies for cross-border transactions has doubled to 13 since Russia invaded Ukraine.

This week’s BRICS summit is no Bretton Woods. All that Russia and its pals have to do is move a relatively small number of sanctions-related transactions beyond America’s reach. Still, many are aiming higher. Next year the BRICS summit will be held in Brazil, chaired by its president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who fulminates over the power of the greenback. “Every night I ask myself why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar,” he said last year. “Who was it that decided?”