4 mins read

America’s Awkward Energy Insecurity Problem

With the (sort of) end of Russian uranium imports, a challenge looms: How to fuel the next generation of reactors?

35 mins read

This brief provides a detailed analysis of a first-of-its-kind, publicly available repository of U.S. think tank funding — www.thinktankfundingtracker.org. The repository tracks funding from foreign governments, the U.S. government, and Pentagon contractors to the top 50 think tanks in the United States over the past five years. It serves as a vital research guide for anyone wishing to learn more about the funding sources of prominent U.S. think tanks.

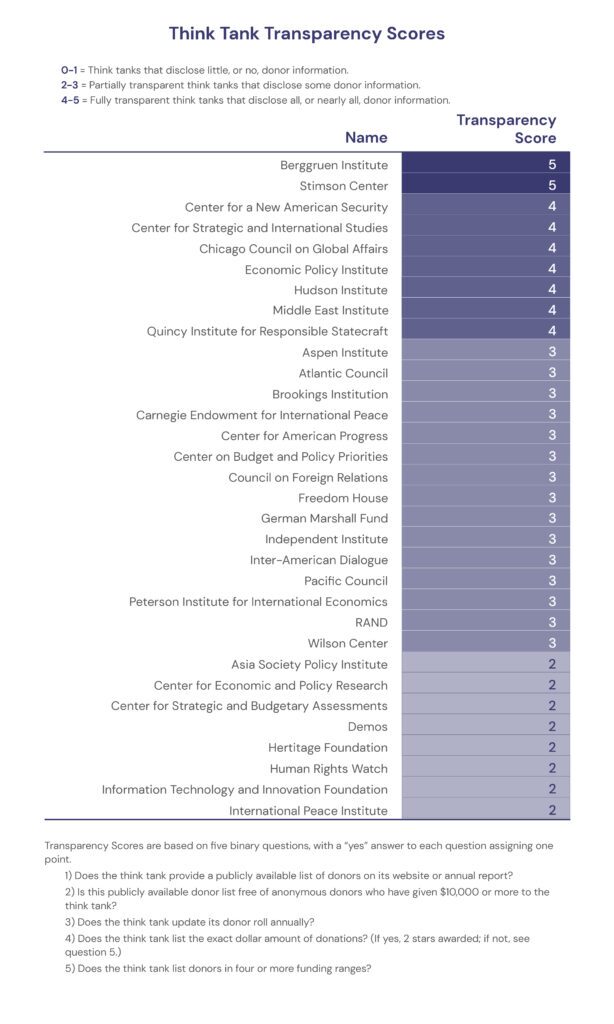

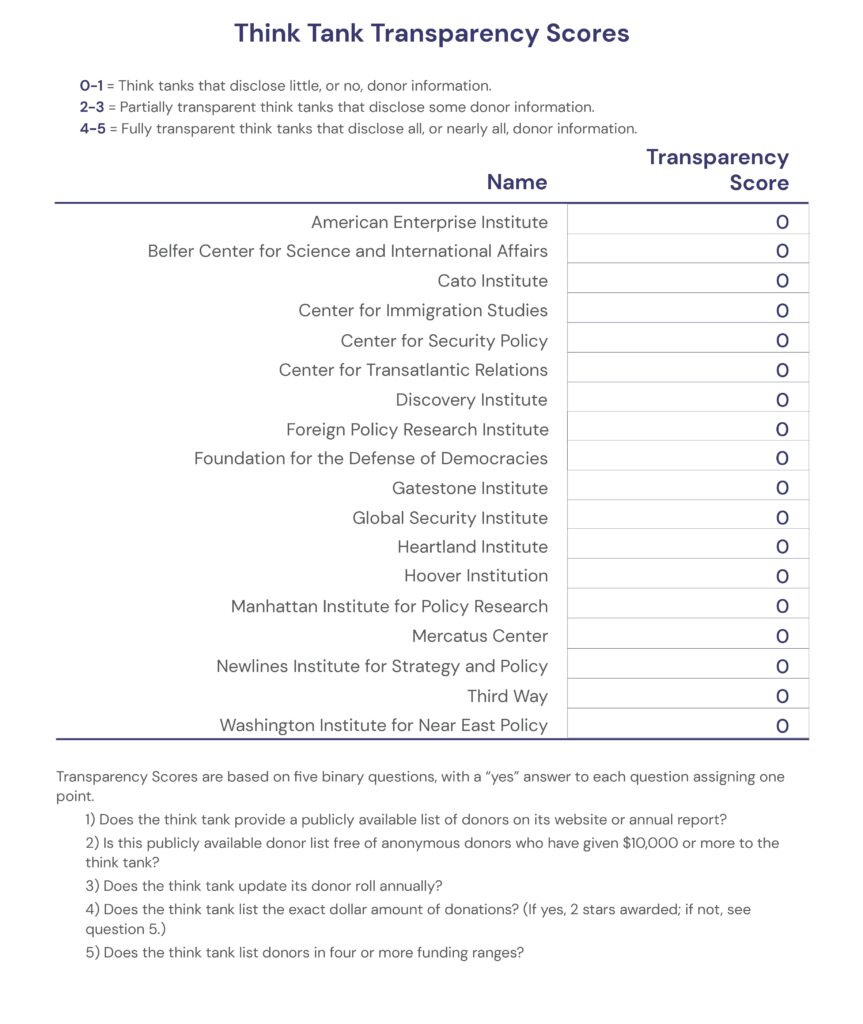

The repository gives a five-point transparency score to each of the top 50 think tanks in the U.S., a scale created by the authors based on five binary questions. Based on this criteria, nine of the top 50 think tanks (18 percent) are fully transparent, while 23 think tanks (46 percent) are partially transparent. Most concerning, the remaining 18 think tanks (36 percent) are “dark money” think tanks, entirely opaque in their funding without revealing donors.

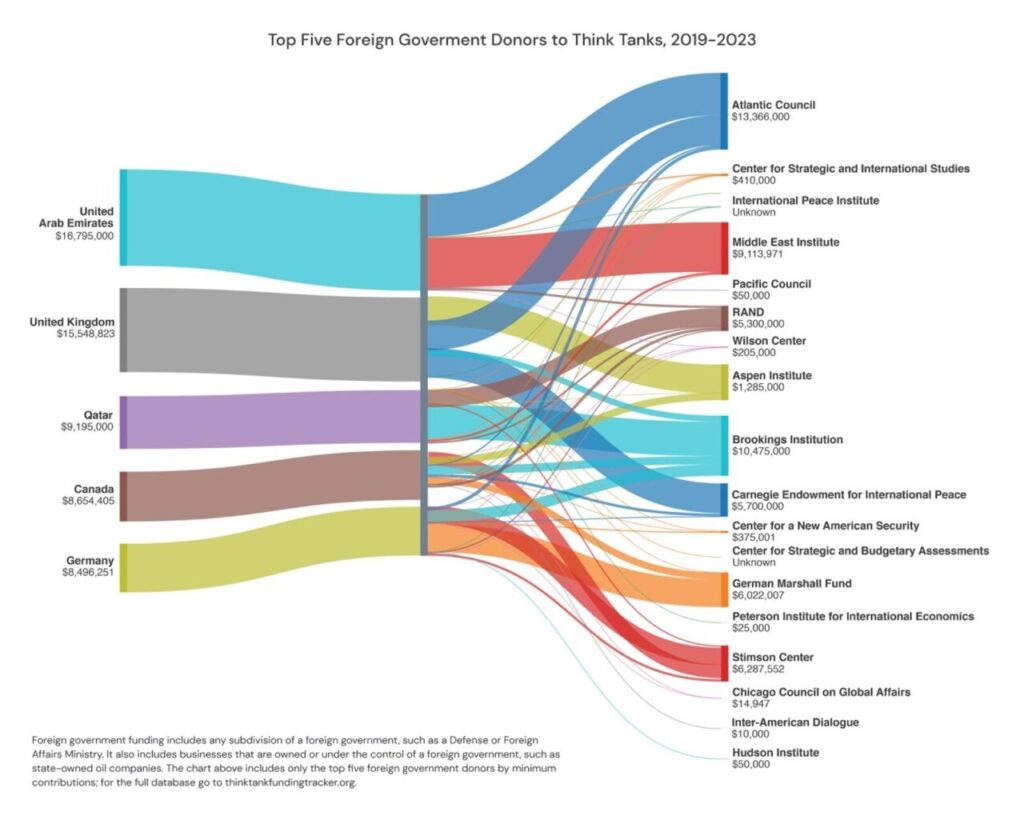

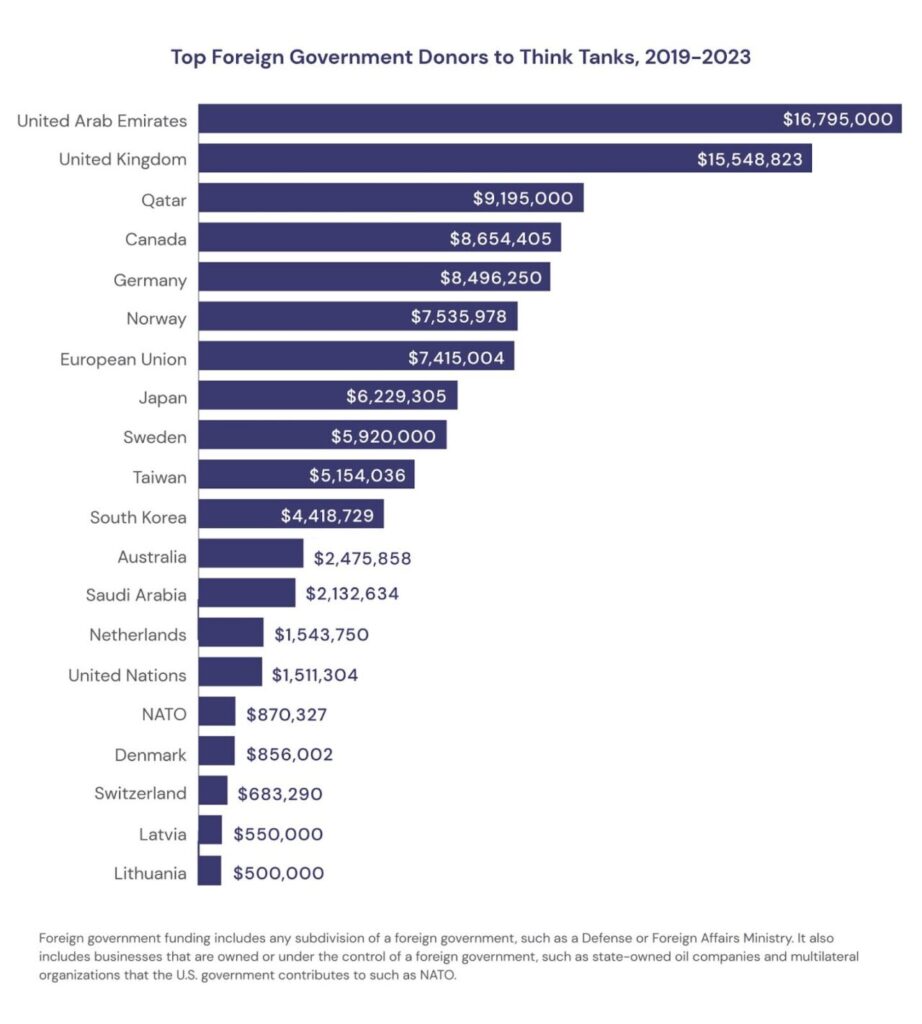

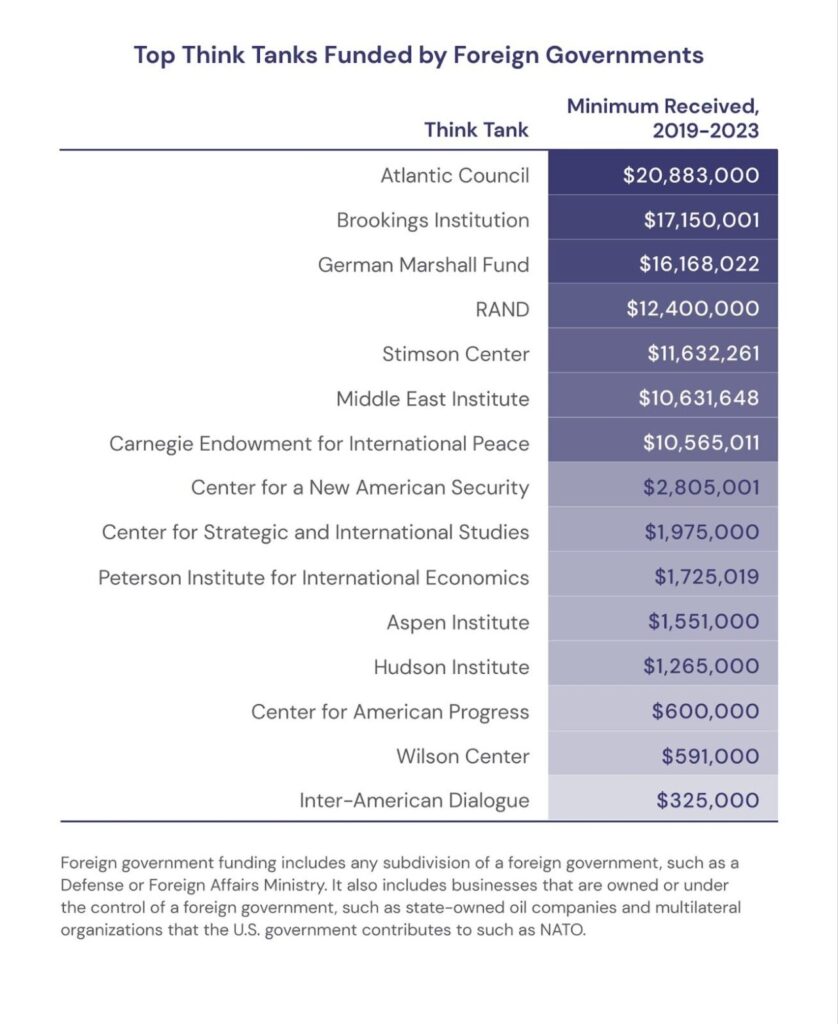

In the past five years, foreign governments and foreign government-owned entities donated more than $110 million to the top 50 think tanks in the United States. The most generous donor countries were the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Qatar, which contributed $16.7 million, $15.5 million, and $9.1 million to U.S. think tanks, respectively. The Atlantic Council, Brookings Institution, and German Marshall Fund received the most money from foreign governments since 2019: $20.8 million, $17.1 million, and $16.1 million, respectively.

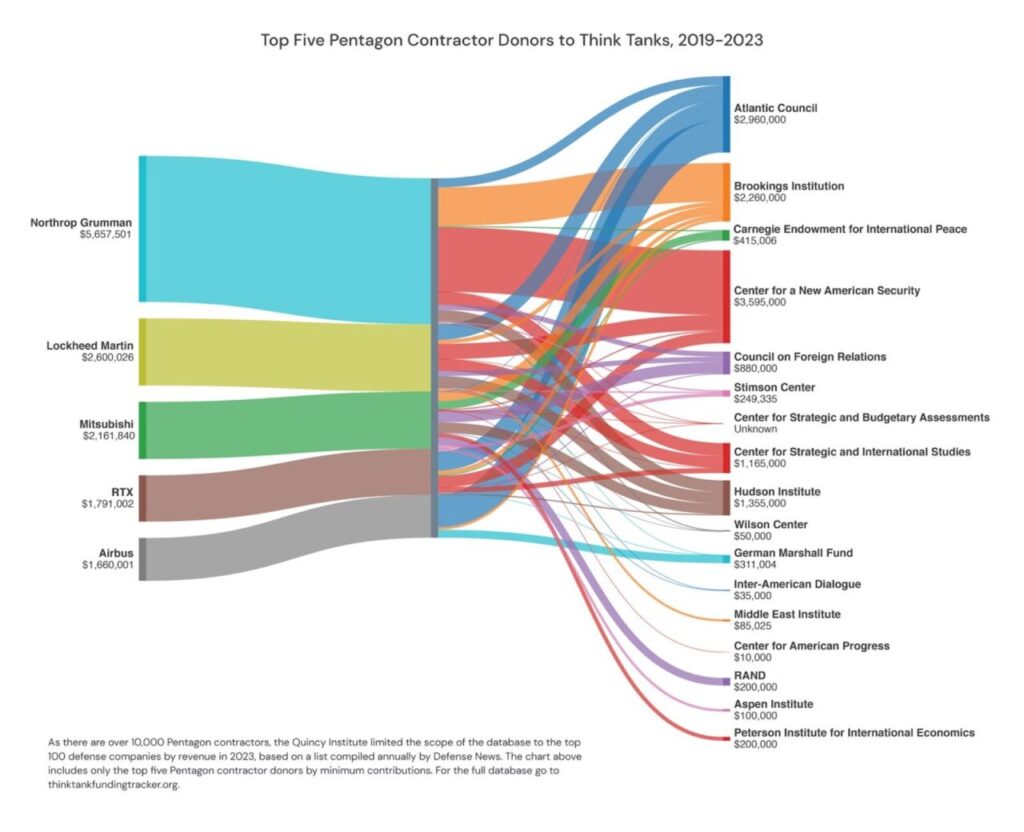

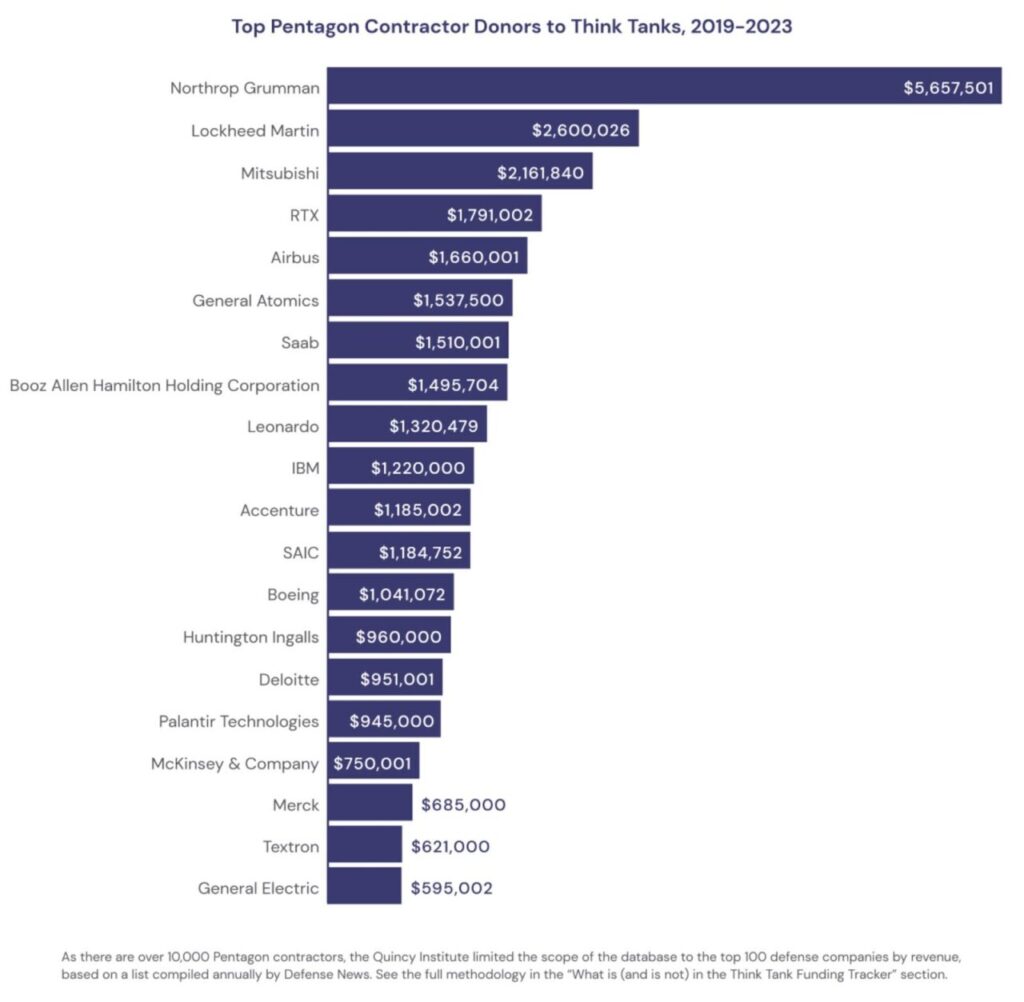

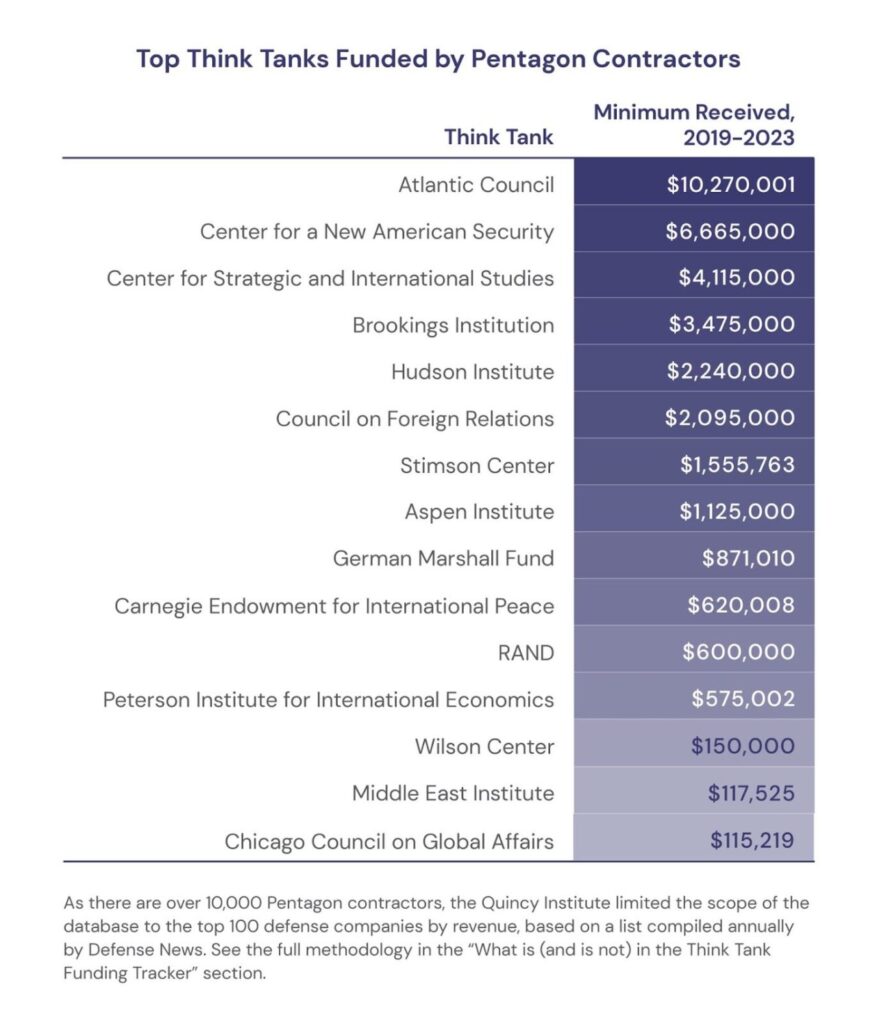

In that same period, the top 100 defense companies have contributed more than $34.7 million to the top 50 think tanks. The top donors include Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and Mitsubishi, which provided $5.6 million, $2.6 million, and $2.1 million, respectively, to the tracked think tanks between 2019 and 2023. The Atlantic Council, Center for a New American Security, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies were the top recipients of Pentagon contractor money: $10.2 million, $6.6 million, and $4.1 million, respectively.

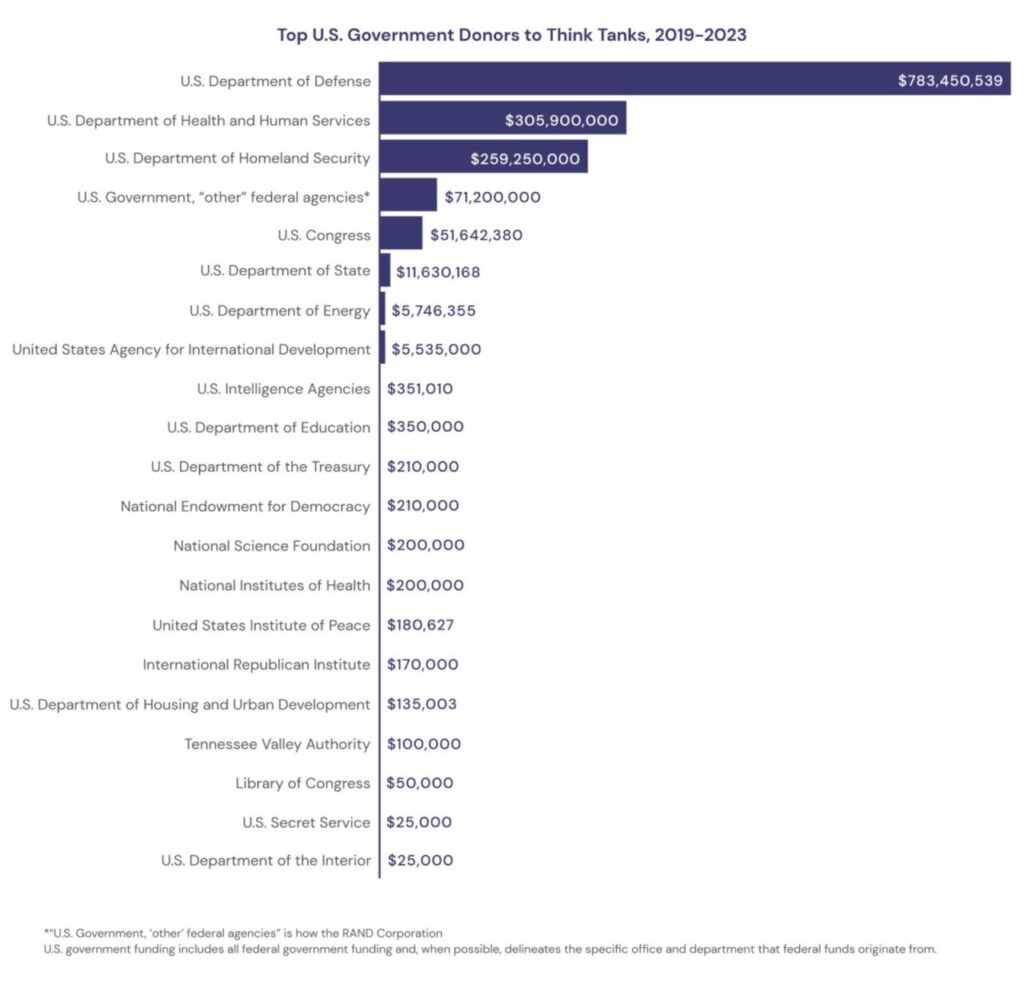

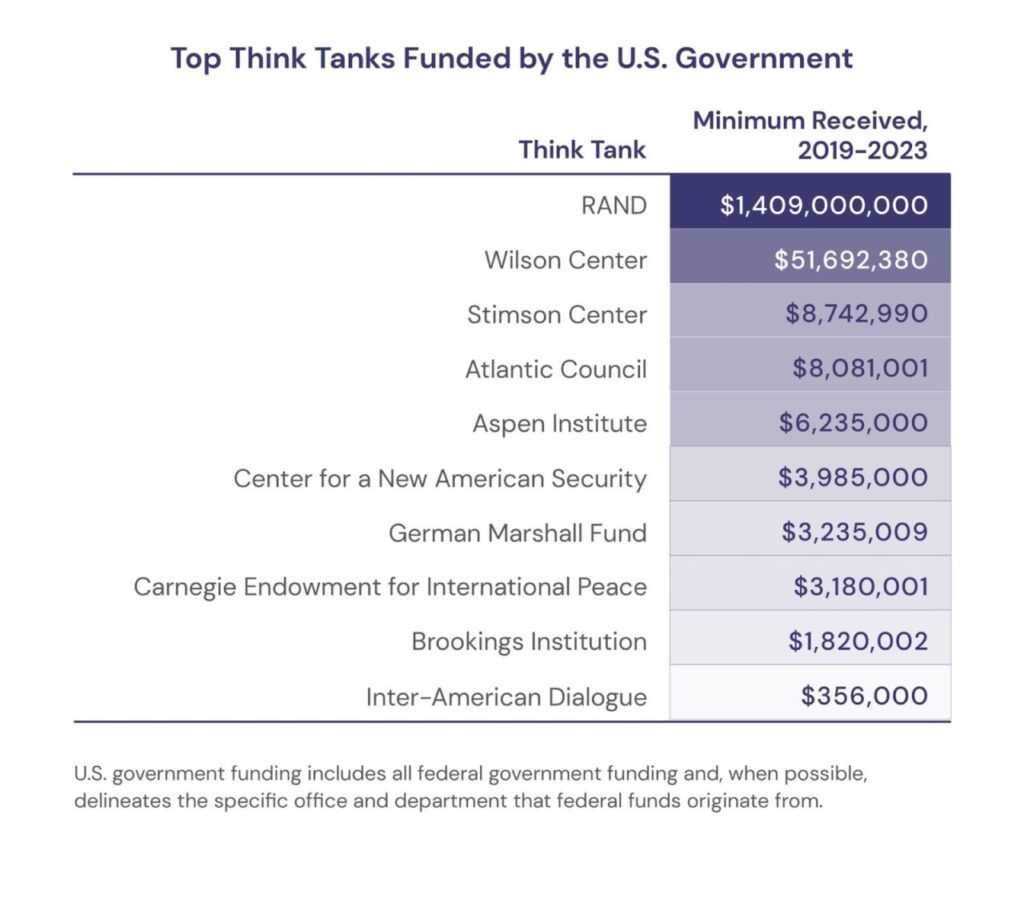

The U.S. government has directly given at least $1.49 billion to American think tanks since 2019. However, the vast majority of this funding — $1.4 billion — goes to the Rand Corporation, which works directly for the U.S. government.

While think tanks exist to produce independent analysis, the prevalence of special interest funding raises questions of intellectual freedom, self-censorship, and perspective filtering. This is compounded by instances in which individual researchers simultaneously hold positions at a think tank and a given foreign government or corporation, a clear potential conflict of interest.

Moving forward, this brief contains a set of recommendations for various actors:

For media: Adopt a professional standard to report any conflicts of interest with sources discussing U.S. foreign policy.

For Congress: Pass legislation requiring all nonprofit organizations that seek to influence public policy to publicly disclose all of their corporate, U.S. government, and foreign government donors above $10,000, and improve the conflict of interest disclosure requirements for congressional witnesses.

For the Department of Justice: Provide clearer guidelines surrounding what think tanks not registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act can do on behalf of their foreign donors.

For think tanks: End pay-to-play research and proactively move toward identifying conflicts of interest.

Think tanks play an enormous role in influencing U.S. public opinion and public policy. Think tank scholars are often the subject matter experts you see on television, hear on the radio, and see quoted in the nation’s top print media outlets. Largely outside of public view, they advise Congress and the executive branch on pending legislation, write questions for congressional hearings, testify at those hearings, and even help draft legislation. While think tank scholars can play an important role as independent researchers, some think tank work more closely resembles public relations and lobbying than research.

Think tanks are increasingly reliant on special interests and governments — both the U.S. and foreign governments — for funding. A growing body of evidence suggests that funding often comes with strings attached, leading to censorship, perspective filtering and, in rare cases, even outright pay-for-research arrangements with donors. Donors are often aware of these benefits. As one internal report from a foreign government noted: “Funding powerful think tanks is one way to gain such access, and some think tanks in Washington are openly conveying that they can service only those foreign governments that provide funding.”1

Yet, despite this link between funding sources and sympathetic policy recommendations, think tanks are not required to disclose their funding publicly. Even relatively transparent think tanks can obfuscate funding sources by allowing anonymous donations, reporting overly broad funding ranges, or simply burying financial information.

This has contributed to a crisis of public confidence in think tanks. Less than half (48 percent) of respondents to a 2022 U.S. public opinion survey believe “think tankers and public policy experts” are “valuable” to society.2To put that in perspective, medical doctors (82 percent), scientists and engineers (79 percent), and even much-maligned lawyers (60 percent) were seen as more valuable than think tankers. Why is the public so skeptical of think tanks and policy experts? According to the survey, “suspecting the expert may have a hidden agenda” was the No. 1 reason respondents cited, followed closely by a “lack of transparency around who is funding the expert.”3

Nonetheless, journalists, policymakers, and think tank experts themselves have largely ignored the public’s concerns. When interviewing a think tank analyst, it is not yet common practice for journalists or news anchors to mention potential conflicts of interest. Nor is it common practice for think tank representatives to disclose potential conflicts of interest in funding when testifying in front of Congress, leaving out relevant context for policymakers. In short, we know that think tank funding matters immensely in its possible impacts on think tanks and the public’s trust in them, yet there is extraordinarily little publicly available information about think tank funding.

For all these reasons, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, QI, is launching the Think Tank Funding Tracker — the first publicly available repository of U.S. think tank funding. This new website and database — publicly available at www.thinktankfundingtracker.org — tracks funding from foreign governments, the U.S. government, and Pentagon contractors to the top think tanks in the United States over the past five years.

The Think Tank Funding Tracker will serve as a resource for journalists, academics, policymakers, and everyday Americans who want more information about the funding of think tanks. Acknowledging funding sources or potential conflicts of interest does not impugn the intellectual independence of the 50 think tanks listed in this publicly available database. Instead, it offers relevant information for individuals to make fully informed judgments.

This report proceeds in four parts:

1. What is (and is not) in the Think Tank Funding Tracker.

2. What we found: Think tank funding by the numbers.

3. Why think tank funding matters.

4. Recommendations to rebuild trust in the think tank sector.

To create the Think Tank Funding Tracker, we collected self-reported information from think tank annual reports and donor roll disclosures. There are currently more than 1,000 think tanks in the United States. To keep the scope of this analysis manageable, we narrowed our list to the 50 most influential. QI took the list of the top think tanks from Academic Influence, a team of academics and data scientists.4Academic Influence compiles its list by aggregating academic citations, tracking the attention think tanks receive, and weighing their merits against other information sources. We substituted non–U.S. think tanks in the Academic Influence list with foreign policy-focused think tanks in the United States, which have similarly high media and public policy profiles.

Within this list of 50 think tanks, the Think Tank Funding Tracker collects data from three categories: foreign government funding, U.S. government funding, and Pentagon contractor funding. These donor categories were chosen for several reasons. First, think tanks receive funding from an extraordinary variety of sources, including individual donors, foundations, and nearly every private industry in the United States. Analyzing all of these donors was well beyond our available resources. Second, QI aims to “expose the dangerous consequences of an overly militarized American foreign policy,” which is a foreign policy that benefits Pentagon contractors and many foreign governments.5While there’s ample evidence of these actors’ investments in lobbying, public relations, and similar influence efforts leading to more militarized U.S. foreign policy decisions, there’s much less understanding of how their contributions to think tanks help achieve donors’ objectives.6The Think Tank Funding Tracker and this report should begin to fill that gap, providing a resource to better examine how funding can influence think tanks.

Most think tanks provide funder lists in ranges rather than specific amounts. The Think Tank Funding Tracker provides the exact donation figure if it is disclosed but otherwise includes a range for each transaction. For all total dollar amounts, the tracker sums the lower end of any range provided to present the most conservative estimate of think tank funding.

QI contacted every think tank in this database and offered them the opportunity to add additional information and, in some cases, offer comments on why the think tank was transparent or was not disclosing donor information.

In the Think Tank Funding Tracker, foreign government funding means funds from any subdivision of a foreign government, such as a defense or foreign affairs ministry. The database includes businesses that are owned or under the control of a foreign government — such as state-owned oil companies — and two multilateral organizations that the U.S. government contributes to: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, and the United Nations, U.N. It does not include privately owned foreign businesses or donations from foreign individuals.

U.S. government funding includes all federal government funding and, when possible, delineates the specific office and department that federal funds originate from. The database does not include contributions from state and city governments and municipalities, which make up only a handful of small donations.

As there are over 10,000 Pentagon contractors, we limited the scope of the database to the top 100 largest defense companies by revenue in 2023, based on a list compiled annually by Defense News.7We broadened this list to add nine more Pentagon contractors that reportedly have classified Pentagon contracts, intelligence community contracts, or make significant contributions to think tanks: McKinsey, IBM, Palantir, Boston Consulting Group, Deloitte, General Atomics, Merck, Accenture, and the MBDA.

As previously mentioned, think tanks are not required to publicly disclose information about who funds them. Think tanks that disclose donors have adopted widely varying levels of transparency. Popular nonprofit rating systems like Charity Navigator and Guidestar, while useful for potential donors, do not measure nonprofits’ funding transparency. To our knowledge, the only organization that has done this on a large scale is Transparify, which “provides the first-ever global rating of the financial transparency of major think tanks,” according to its website.8Transparify last updated its transparency ratings in 2018. The Think Tank Funding Tracker hopes to build upon that and provide updated transparency ratings for the top think tanks in the United States.

Transparency is a scale rather than a dichotomy and could potentially incorporate an immense variety of factors. To simplify this process and provide an objective scale of funding transparency, we used a simple five-question test to determine each think tank’s Think Tank Transparency Score. Each question informs the degree of transparency of a think tank and provides the public with a general sense of how transparent a think tank is about its funding. These five questions are binary, with a “yes” answer to each question assigning one star:

Think tanks are rated on a scale of one to five, with five representing those that are most transparent (see chart below).

Only ten think tanks received a Think Tank Transparency Score of four or five. These think tanks display a commendably high level of transparency, allowing lawmakers, journalists, and the public to better understand the source(s) of their funding.

The Berggruen Institute, for instance, is funded by a single donor, the Nicolas Berggruen Charitable Trust.9Nils Gilman, chief operating officer of the Berggruen Institute and a former non-resident fellow at the Quincy Institute, explained via email that “we have a single donor who is singularly committed to exploring the intersection between philosophy and governance, and who greatly appreciates both the importance of transparency about funding sources and the value of independence from external donor influence.”

The Stimson Center may be a more representative example of the think tank industry since it accepts funding from dozens of sources. Yet, unlike much of the think tank industry, the Stimson Center is fully transparent about its funding. As part of its funding policy, Stimson “provides a complete list of donors and funders for the most recently completed fiscal year. This list of donors and funders is published yearly.”10In almost all cases, Stimson lists exact dollar amounts of donations.11For these reasons, Stimson earned a five-star transparency score. The Middle East Institute and Chicago Council on Global Affairs are the only other think tanks we analyzed that list exact dollar amounts of contributions.

Several prominent think tanks, such as the Center for Strategic and International Studies, CSIS, received a four-star transparency score. Based on these authors’ analysis of congressional hearings, CSIS was called upon more than any other think tank to provide testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives over the past two sessions of Congress. This level of transparency enables lawmakers to verify funding sources for these witnesses if they so choose. The Center for a New American Security, the Economic Policy Institute, the Hudson Institute, and the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft round out the list of think tanks receiving four-star transparency scores.12

To be sure, there are also means of transparency that the Think Tank Transparency Score does not track. For instance, the Think Tank Transparency Score does not track how easily accessible funding information is to the public — a spectrum that ranges from front and center on a think tank landing page to scrubbed pages only accessible via digital archives. It remains common practice for some think tanks to update donor rolls annually rather than maintaining separate pages for distinct funding periods, meaning the public has to use internet archives to access older funding information.

Additionally, our Think Tank Transparency Score does not track how transparent think tank analysts are when testifying in front of Congress. Think tank analysts are asked to fill out forms called Truth in Testimony disclosures when testifying in front of committees in the House of Representatives.13While many witnesses simply ignore this requirement to disclose potential conflicts of interest, others are commendably forthcoming. For instance, when testifying at a hearing about the Replicator Program — a new Department of Defense initiative to develop autonomous swarms of drones — Hudson Institute Senior Fellow Bryan Clark disclosed industry funding from Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and General Atomics, companies that have a stake in the outcome of the hearing.14Typically, more transparent think tanks are more forthcoming in disclosing potential conflicts of interest on these forms.

Unfortunately, most of the top think tanks in the United States offer less funding transparency than think tanks with a four-star or five-star Think Tank Transparency Score. A plurality of think tanks within the database are partially transparent, meaning they make some effort to disclose donor information, but not with the same level of specificity as the fully transparent think tanks.

For instance, partially transparent think tanks accept anonymous contributions. In 2023 alone, there were at least $14 million in contributions labeled “anonymous” across the top 50 think tanks analyzed in this paper. Listing anonymous contributions remains a common practice among many prestigious Washington think tanks. The Brookings Institution, for example, accepted “anonymous” contributions from nine sources that contributed just under $4 million combined in 2023.15Brookings’ financial transparency policy states they do not grant anonymity for corporations or governments, but grant anonymity on a case-by-case basis for foundations and individuals.16

Meanwhile, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, CBPP, allows any donor to request anonymity. CBPP listed three anonymous donors that contributed over $500,000 each in its 2022 annual report.17Shannon Buckingham, senior vice president for communications and senior counsel at CBPP, explained via email that “if a donor requests confidentiality, we honor that request except in cases where we are required by law to provide identifying information.” The Peterson Institute for Economics lists a handful of anonymous donors, including two at its highest range: $250,000 and above. Steven Weisman, the vice president of publications at Peterson, explained via email that “in a miniscule number of cases, donors ask not to be identified.”

Secondly, many think tanks list out wide ranges of donor categories rather than exact amounts. By listing out funding in ranges, think tanks can conceal the degree of funding from specific sources. For instance, the Council on Foreign Relations, CFR, lists three ranges for its corporate membership program: Gold ($100,000), Silver ($75,000), and Bronze ($50,000).18However, it’s anyone’s guess as to the amount donors in the Gold category actually contributed. Whether a donation is $100,000 or $10,000,000, it is recorded as the same. Given that CFR is one of the largest think tanks in the United States — reporting $107 million in revenue in 2023 — its funding ranges should be more informative.19

Although it may be incomplete, partially transparent think tanks still offer a useful window into their funding patterns. Releasing a donor list at all is the biggest step a think tank can take toward establishing credibility if aspects of its disclosure could be improved.

Out of the 50 think tanks analyzed in this paper, 18 of them are almost entirely opaque when it comes to donors and received a score of zero. Due to federal regulations, think tanks do report some information on their Form 990 — an Internal Revenue Service form that all nonprofits are required to complete — such as a broad breakdown of revenue sources (i.e., what percentage of revenue comes from contributions, sale of assets, or investment). However, think tanks are not obligated to publicly identify the sources of donations, which typically make up the vast majority of their funding.

This “dark money” makes it virtually impossible to determine think tank funding sources and determine conflicts of interest, real or perceived. In rare cases, there is public reporting of dark money sources. In others, the think tanks themselves accidentally let slip their funding sources. During an American Enterprise Institute, AEI, event, for example, the moderator noted that Pentagon contractors fund the think tank by saying, “We’d be remiss if we didn’t mention that both Lockheed [Martin] and Northrop [Grumman] provide philanthropic support to AEI. We are grateful for that support.”20Yet, AEI is remiss in that it does not publicly disclose any donors on its website or in its annual reports.

Some of these dark money think tanks, like AEI, are among the most prominent think tanks testifying in front of Congress. In 2021, Quincy Institute Senior Advisor Eli Clifton reported that less than 30 percent of think tank-affiliated witnesses before the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, HFAC, fully disclosed their donors.21That trend continues today. Between 2021 and 2024, 34 percent of all think tank witnesses before HFAC came from dark money think tanks.22For example, 11 analysts from the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, which does not disclose any information about its donors, testified to HFAC during that period.

Many think tanks with little or no funding transparency that we reached out to for comment professed that their scholars maintain complete intellectual independence, academic freedom, or similar insulations from donor pressures. However, there is no way for the public, journalists, or Congress to verify those claims from dark money think tanks. By making their funding transparent, think tanks could entrust the public to audit claims of intellectual independence. Revealing funding sources is not only beneficial to lawmakers who rely on outside research but can also establish that think tanks are a trustworthy and transparent source of information and analysis. As we discuss in greater detail below, this is precisely why think tanks should be required to disclose their donors.

Foreign governments and foreign government-owned entities donated over $110 million in the past five years to the think tanks analyzed in this report. These contributions came from 54 different countries. Many think tanks have implemented policies against accepting foreign government funding, including several dark money think tanks, such as AEI and the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Despite this, at least 65 percent (21 of 32) of the think tanks that publish a donor list have accepted foreign government funding since 2019, more than the number of think tanks that accepted Pentagon contractor and U.S. government funding. A majority of the top donor countries are U.S.–allied democracies, with a few notable exceptions, such as the United Arab Emirates, UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Since there is no legal requirement to disclose these contributions, think tanks may, in some cases, anonymize contributions from non-democratic countries for fear of sullying their reputations. Thus, these figures should be seen as a floor, not a ceiling, of foreign government funding at top think tanks in the United States. From 2021 to 2024, 89 percent of witnesses affiliated with think tanks that testified before HFAC are from organizations that take contributions from foreign governments.23

Since 2019, top Pentagon contractors have contributed more than $34.7 million to the 50 U.S. think tanks included in this study. Of the think tanks that publish a donor roll, 62 percent (20 of 32) received funding from those contractors, though the real number is likely higher given that many think tanks publish a donor role but do not list corporate contributions. The Heritage Foundation, which does not publish a corporate donor roll, previously accepted Pentagon contractor funding but says it no longer does. According to Heritage Foundation Vice President of Communications Rob Bluey, last year “Heritage made the decision to refuse funding from the defense industry, which protects our ability to provide independent analysis without even the perception of influence on the part of any defense contractor.”24

From 2021 to 2024, 79 percent of witnesses affiliated with think tanks that testified before HFAC represent organizations that take donations from the top 100 Pentagon contractors.25Yet those analysts have no requirement to inform lawmakers about that potential conflict of interest, despite testifying on defense policy that could directly benefit those Pentagon contractor donors.

The U.S. government contributed at least $1.49 billion to U.S. think tanks from 2019 to 2023. The Department of Defense is far and away the top donor in the Think Tank Funding Tracker, with the vast majority of these contributions going to the RAND Corporation (more than $1.4 billion). RAND is unique on this think tank list in that it works directly for the U.S. government, operating several federally funded research and development centers. RAND served as the prototype for think tank funding relationships for much of the Cold War and has a robust conflict of interest policy in place. As part of its policy, it does not accept “funds” (i.e., project sponsorship or philanthropic support) from firms or segments of firms whose primary business is that of supplying equipment, materiel, or services to the U.S. Department of Defense. Beyond RAND, just under half (40 percent) of the think tanks in this database accepted contributions from the U.S. government, typically from national security agencies. The other top recipients are the Stimson Center, the Atlantic Council, and the Aspen Institute. Since the Think Tank Funding Tracker collects self-reported information from think tank annual reports and donor roll disclosures, outside information from other sources, such as investigative journalists, was omitted in this analysis.

Think tanks have played, and continue to play, an important role in the creation of U.S. foreign policy. Originally formed in response to a need to overhaul machine politics, think tanks offered analysis and expertise to policymakers. Robert Brookings, the businessman who founded the Brookings Institution, claimed his new policy institute was “the first private organization devoted to the fact-based study of national public policy.”26Others, including the Hoover Institution and the Council on Foreign Relations, followed suit. As historian Stephen Wertheim documents in his book, Tomorrow the World, the Council on Foreign Relations played a crucial role in planning for the United States to lead a new international order after World War II.27Brookings, meanwhile, helped design the Marshall Plan.28Later, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara relied heavily on the RAND Corporation and their “whiz kids” to inform the statistics-based logic and strategy of the Vietnam War. There have always been prevailing incentive structures, but think tank research was more academic and reliant on longer-term funding, often from the U.S. government itself. For many decades, this was the model for how most think tanks operated in the United States.

Today, the landscape is quite different. Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, the number of think tanks ballooned as they became more politically active and their funding models shifted toward short-term sources.29Special interests dominate think tank donor rolls today, and many think tanks even openly advertise the influence that foreign governments and private corporations can gain through sponsorship programs. Kjølv Egeland and Benoît Pelopidas, the authors of a study of think tanks, wrote that “the most generous funders exercise significant influence on the evolution of the foreign policy marketplace of ideas by affecting which questions are asked and which expert milieus are enabled to thrive.”30If think tanks are reliant on Pentagon contractors and there is no counterbalancing voice, it can lead to an entire sector singing in chorus for things that will benefit Pentagon contractors — most notably, ever-increasing defense budgets and foreign conflicts.

As two researchers, Campbell Craig and Jan Ruzicka, put it in a 2022 study on the institutions that support nuclear weapons, those that “support the extant nuclear order enjoy funding, political support, and policy relevance; those who deviate from it do not,” which suppresses the rise of alternative ideas to the status quo.31In Egeland and Pelopidas’ follow-up study, all 45 think tanks in their sample acknowledged funding from either nuclear defense contractors or governments with an interest in the continued deployment of nuclear weapons and found that “such stakeholder funding has real effects on intellectual freedom.” Though impossible to quantify exactly, understanding these relationships between think tanks and their donors matters.32

Egeland and Pelopidas, through interviews with dozens of current and former think tank staff, as well as grant managers, found compelling evidence that funding can lead to self-censorship and donor-directed censorship in some cases.33“Self-censorship is the greatest threat to our democracies in the West. A lot of think tank experts posture as experts with complete academic freedom — this is absolutely not the case,” one think tank scholar explained to the authors of the study. A grant manager who provides funding to think tanks explained how the process works: “The recipient knows they might not be funded next time around if they’re very disloyal.” A former think tank analyst went even further, telling Egeland and Pelopidas: “what we were producing was not research, it was a kind of propaganda.” Given the scathing commentary from interviewees, the conclusion of this analysis is quite blunt: “Scholars, media organizations, and members of the public should be sensitized to the conflicts of interest shaping foreign policy analysis generally and nuclear policy analysis specifically.”34

In some cases, funders even offer financial compensation for think tanks to produce specific reports. For instance, in 2016, the Center for a New American Security, CNAS, received $250,000 to produce a private report on the Missile Technology Control Regime, MTCR, an informal regime that had been a roadblock to the UAE’s goals of importing certain weapons, such as drones.35 According to reporting from The Intercept, then-CNAS CEO Michèle Flournoy sent an email to UAE Ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba saying: “Yousef: Here is the CNAS proposal for a project analyzing the potential benefits and costs of the UAE joining the MTCR, as we discussed. Please let us know whether this is what you had in mind.”36When the report was finalized, Otaiba circulated it among high-ranking Emirati officials and wrote back praising the study: “I think it will help push the debate in the right direction.”37 In August 2020, the United States announced plans to sell armed drones to the UAE.38

While these smoking guns of influence and pay-to-play funding for specific research arrangements do exist, they are rare. Far more common are instances of perspective filtering. After the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the Center for American Progress, CAP — which previously received over $500,000 annually from Saudi Arabia’s ally, the UAE — initially drafted a statement condemning the killing and called for consequences for Saudi Arabia. However, after an email exchange with national security experts within CAP, the organization dropped the call to action and simply called for the United States to take “additional steps to reassess” its relationship with Saudi Arabia.39

Daniel W. Drezner, a professor of international politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, points out that funding think tanks “can be as valuable as spending on lobbyists” because it is less regulated.40Under the Lobbying Disclosure Act, LDA, firms representing corporations have to fill out registration statements, disclose prior government experience, and list which bills they lobbied in favor of. Under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, FARA, firms lobbying on behalf of foreign governments have to disclose which offices they contacted, a description of their political activities, and the informational materials they circulate to influence policy. All of this, however imperfect at times, is regulated. At least one foreign government — Israel — has reportedly considered creating a think tank-like nonprofit organization specifically to avoid disclosure requirements under FARA and the LDA.41

Some think tanks even openly advertise the influence and access available to donors. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy does not publicly disclose any information about its donors but publicly advertises that those who give the organization $25,000 or more “are afforded unique opportunities to access our work, receiving invitations to intimate regional events, private dinners, and special visits to key policy venues in Washington.”42The Wilson Center advertises a dedicated point of contact with a member of the Wilson Center’s leadership team, opportunities to host “intimate and private salon discussions” with senior-level program directors on issues of interest, and “private off-the-record events across the country” for $100,000 annually.43

The Atlantic Council’s website similarly lists some of the benefits of becoming a “strategic partner.” These benefits include private dinners, briefings, an annual roundtable with the CEO and president, and a partnership manager to oversee the company’s engagement with the Atlantic Council. The Atlantic Council describes its relationship with strategic partners as a “deeply collaborative endeavor.”44

While access and collaboration are not inherently problematic, they can pave the way for donor control over outcomes or censorship of research unfavorable to donors. On one occasion, leaked emails showed that the Atlantic Council gave UAE Ambassador Al Otaiba the opportunity to provide comments on a draft report about U.S. policy toward Iran.45Barry Pavel, head of the Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security at the Atlantic Council at the time, pointed to its corporate partners program: “We work through these issues with corporate partners, with government partners, with individuals, not as much with foundations, they don’t really weigh in like that. … We hear their opinions when they’re rendered and then we give them to the authors of the papers.” According to Pavel, Otaiba was not the only donor who reviewed the report. The author of the report accepted some of Otaiba’s smaller changes but stuck to her main argument. “My understanding is [foreign governments] have others in their portfolio that do the more directed work,” Pavel told The Intercept.46

There may also be potential conflicts of interest stemming from individual researchers. It is common for an expert at a think tank to simultaneously act as an advisor to the government, serve on the board of a private corporation, or both. These multiple positions can blur the lines of think tankers constantly switching in and out of these roles.47For instance, James Taiclet currently serves as the CEO of Lockheed Martin, which receives more money from the Pentagon than any other firm in the world. Taiclet is also on the board of directors of the Council on Foreign Relations.48 Given that Taiclet’s company and salary are largely reliant on Pentagon contracts, this could present a conflict of interest with his role guiding a major foreign policy think tank.49

Some think tank board members and fellows even work for foreign governments simultaneously. James Jones Jr., for example, is a former national security advisor to President Barack Obama who has served on the Board of Trustees for the Center for Strategic and International Studies since 2011.50In 2016, Jones applied for authorization to work on behalf of Saudi Arabia, and owns two consulting firms that held contracts advising the Saudi Defense Ministry.51Daniel Vjadich, the president of Yorktown Solutions, was dubbed the “man fighting for Ukraine in D.C.,” by Politico in 2022 for his FARA–registered work representing Ukrainian interests in the United States.52At the same time Vjadich was lobbying feverishly for Ukraine, he was a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.53

Funding relationships are complex. Donors could seek out individuals and institutions that are already aligned ideologically, outsource research on specific subject matter, or encourage further studies in a less understood area. None of the data found in the Think Tank Funding Tracker implies any sort of causation. Instead, it provides a tool for users to identify potential conflicts of interest and help unpack some of these complex funding relationships.

Think tanks play an important role in the political process. Think tank experts provide valuable insights — regional experience, subject matter expertise, data analysis, and much more. Lawmakers rely on these outside experts to conduct resource-intensive original research to help shape U.S. policies. As objective as think tanks claim and, perhaps, aspire to be, they rely on funders for their work and, in some cases, funding comes with strings attached. Funding can lead to self-censorship, outright donor censorship and, in rare cases, donors paying for specific research products, which has contributed to a crisis of public confidence in think tanks. One 2018 poll from Cast from Clay found that only 20 percent of Americans trust what think tanks have to say.54But it doesn’t have to be this way. At a time when confidence in government is at a near-record low, think tanks can and should serve the public interest.55

Transparency is the best way to restore trust in the think tank sector. Some journalists have adopted the practice of mentioning foreign government funding of think tanks when interviewing experts. In an article about then–Senator Bob Menendez’s ties to Qatar, The New York Times interviewed Hussein Ibish, a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. The article included the following disclosure in the body of the article: “Like many Washington think tanks, [Ibish’s] research organization has received funding from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — a sign of the depth of Gulf influence in the United States.”56According to one congressional staffer: “If we fix this in Congress, and we actually get testimony that’s uninfluenced by such agendas, we’re going to get better laws, we’re going to get better policy, we’re going to get better hearings.”57

To move toward these goals and, based on the research conducted in compiling this report and the Think Tank Funding Tracker, we offer the following recommendations:

1.) Congress should pass legislation requiring all nonprofit organizations that seek to influence public policy to publicly disclose all of their corporate, U.S. government, and foreign government donors who give above $10,000. This builds on proposals to require think tanks to disclose foreign government funding, such as the Think Tank Transparency Act and the bipartisan Fighting Foreign Influence Act. The Justice Department should be empowered to impose civil penalties on think tanks that do not disclose such information.

2.) Congress should dramatically improve the conflict of interest disclosure requirements for congressional witnesses. Currently, individuals testifying before U.S. Senate committees do not have to disclose any information about potential conflicts of interest. A first step in remedying that is for the Senate to introduce Truth in Testimony forms, as the House has, which require witnesses to disclose any potential conflicts of interest related to the subject of the hearing. Unfortunately, even these forms in the House are often not filed accurately and are sometimes not filed at all. Thus, an important step forward would be for both chambers to enact mandatory disclosure, close the loophole that allows witnesses to testify in their personal capacity, expand the scope of the questions to include all high-level foreign government funding and relevant private conflicts of interest, and to penalize witnesses who offer grossly incomplete or misleading information in their disclosures.

1.) The Department of Justice should provide clear guidelines surrounding what think tanks not registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act can do on behalf of their foreign donors. There is, unfortunately, considerable ambiguity in FARA’s language that has allowed the act to be used as a political weapon against think tanks and other nonprofits. Some members of Congress, for example, have accused the National Resources Defense Council of acting as a foreign agent of China, pointing to its positive engagement with Chinese officials. This is a clear example of FARA overreach, given that these accusations have not produced any evidence of a principal-agent relationship and demonstrate the potential for this ambiguity to be weaponized.60Clarifying this language will better serve to protect think tanks from undue accusations of foreign agent activity, while clearly explaining to think tanks that engage in this type of work that they should register under FARA.

1.) Think tanks must end pay-to-play research. Allowing donors to determine specific research conclusions that would provide a financial or direct material benefit to a funder is the antithesis of the intellectual independence that think tanks should be founded on. Research like this only serves to increase public distrust of the think tank sector.

2.) Think tanks should work to avoid less explicit conflicts of interest and, as an earlier Quincy Institute brief recommended, should “proactively identify instances in which a funder may appear to get obvious benefit from policies endorsed in research work by staff.”61Think tanks should change the conversation away from defending against accusations of real or perceived conflicts of interest and toward proactively avoiding and disclosing conflicts of interest when necessary.

1.) Experts from foreign government-funded and Pentagon contractor-funded think tanks dominate the media landscape. For example, a 2023 Quincy Institute brief found that in articles related to U.S. military involvement in Ukraine, “media outlets have cited think tanks with financial backing from the defense industry 85 percent of the time or seven times as often as think tanks that do not accept funding from Pentagon contractors.”62Rarely, if ever, are these potential conflicts of interest mentioned. As suggested in a previous Quincy Institute brief: “Media outlets should, similarly, adopt a professional standard to report any conflicts of interest with sources discussing U.S. foreign policy. … This information provides important context for evaluating expert commentary and is, arguably, as important as the commentary itself.”63The New York Times has already, at times, adopted this practice.64