6 mins read

For peace in Ukraine, we must defeat the globalist propaganda machine

A million Ukrainians dead, Zelenskyy running a dictatorship, and the US funding it all. The media’s biggest concern? That Trump might stop the war.

10 mins read

KYIV — Ukraine is shrinking.

The war has killed tens of thousands of civilians and soldiers. At least 5 million more have fled and live outside Ukraine, and a fifth of the country — another 5 million people — is under Russian occupation.

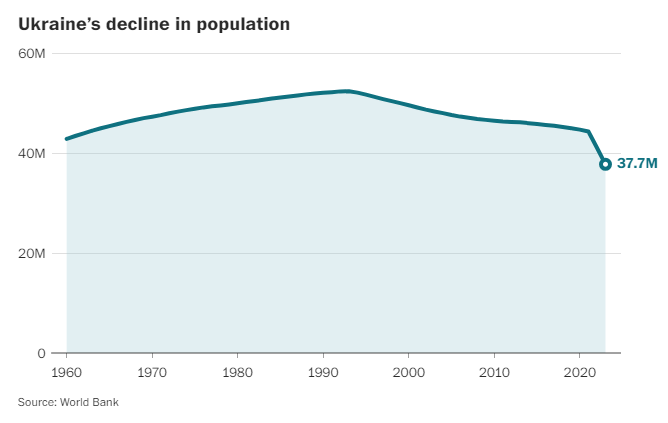

Ukraine’s population at independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 was over 50 million. Now just 31 million live in land controlled by Kyiv. And the number of deaths is nearly three times the number of births, according to the justice minister.

These missing Ukrainians — the ones who have fled, the dead, the occupied — have left a gaping hole in today’s Ukraine that will greatly shape what sort of country will be left when the conflict ends. A diminished population could have a major impact on the country’s economic health, political stability, ethnic makeup and ability to fight wars in the future.

As President Volodymyr Zelensky travels to the United States to meet with President Donald Trump and discuss a deal for the country’s minerals and a possible end to the war, the issue looms in the background.

Reversing the demographic decline is critical and “on par with our victory in the war, achieving a just and stable peace, membership in the E.U. and NATO, and rebuilding the country,” said Mykola Kniazhytskyi, an opposition parliament deputy.

Today, Ukraine’s population, including the areas under Russian occupation, is believed to be just under 36 million, officials say, down from roughly 41 million when the war broke out. These numbers are estimates, however, and could be much lower.

If demographic trends continue, Ukraine’s population is expected to be around 25 million by mid-century and just 15 million in 2100.

To boost the birth rate and preserve ties with those outside the country, the government has introduced a raft of initiatives — from integration hubs for those abroad to keep them apprised of job opportunities back home to free fertility treatment for soldiers and their families.

“The task is to return these families, to return these children and also to motivate Ukrainians to have as many children as possible, so that Ukraine can prosper in its peaceful future after our victory,” Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal said on Ukrainian television in March of last year.

“Every Ukrainian family” should have “no less than three children,” he added.

Ukraine is not alone in its population woes — or in the risks they pose. Across the developed world, countries are experiencing demographic declines. Eastern Europe has witnessed one of sharpest drops because of low birth rates, early mortality and a high rate of emigration, with Russia in particular shrinking.

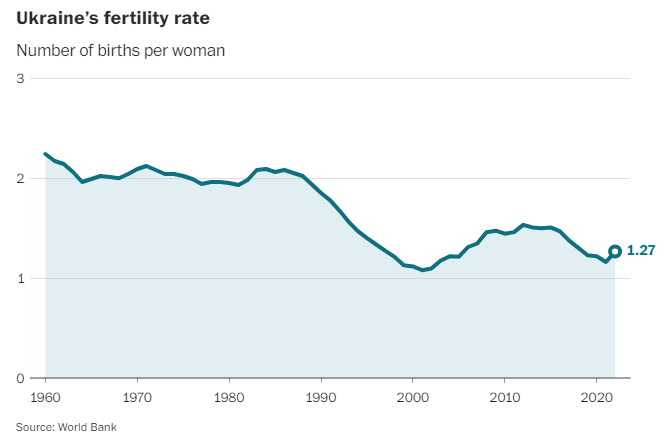

Even before the war, though, Ukraine’s demographic numbers were among the worst in the world. Because of the country’s historically low birth rate, men between the ages of 20 and 30 are today in comparatively short supply.

Ukrainian officials hope to induce those who have left the country to return once the war ends — especially as a large portion of them are young, educated professionals and women in their childbearing years.

Dana Pavlychko belongs to this target demographic. A 37-year-old with an MBA from the University of Oxford, she lives in Germany with her husband, Roman, and their three children, but has no plans to return to Ukraine to live permanently.

“Our kids are definitely not moving back to Ukraine because we are not going to uproot them from a German school system to a Ukraine school system and totally change [their] lives,” Pavlychko said.

Pavlychko said that among her Ukrainian acquaintances living abroad, only about half say that they will return.

“I meet a lot of people who really want to go back,” she said by telephone. “But the desire to go back and the reality of going back is very different. Because the reality of going back is, will there be work? Will there be schools for kids? Will there be health care? Will there be stability considering the political turmoil that will be, with possible elections and what will come after?”

Similarly, a survey published last week by the Center for Economic Strategy in Kyiv showed “less than half of Ukrainian refugees” indicated they would return home.

Borys, a software developer living with his wife and 4-year-old son in Western Europe — who spoke on the condition he be identified by only his first name because of the sensitivity of the issue — said that to return, he needed “a strong, absolute guarantee that Russia won’t attack us.”

“Before the war, I never intended to immigrate,” he said. “If Putin goes and the government changes, it’s not a guarantee, because it’s not Putin who is physically killing Ukrainians,” he said. “This story of Russian-Ukrainian relations is centuries long.”

The Ukrainian government hopes to change these minds, or at least maintain strong ties to this diaspora that will be passed onto their children. In October, Ukraine’s parliament created a ministry devoted exclusively to demographics and relations with the diaspora.

Ukrainian officials announced this year the creation of Unity Hubs in countries where large numbers of refugees reside to help Ukrainians integrate into the communities they live in — providing language lessons, for example — or move back to Ukraine if they wanted, finding them jobs and places to live.

“If we talk about migrants who left after a full-scale invasion, obviously we would like to return 100 percent. We will not return 100 percent,” said Deputy Minister of Social Policy Dariia Marchak. “But we are targeting and aiming to return the maximum number of them.”

Marchak said there was a “huge deficit” in Ukraine’s labor market, but the job opportunities were not widely known. “Our task is to make sure that people who need work in the country and abroad know about the possibilities that exist, in the areas in which these possibilities exist.”

In 2001, Ukraine recorded an average of 1.1 children per woman — well below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 and at the time the lowest in the world. The numbers did improve in subsequent years, but then the war came.

“Birth rates have dropped below 1.0,” the U.N. Population Fund in Ukraine wrote in July on the agency’s website.

“That portion of the population that should be having children, which can have a family, has greatly decreased,” said Vitaliy Radko, a reproduction specialist at the Mother and Child fertility clinic in Kyiv. Large numbers of “women of reproductive age” live outside Ukraine, he said, and men “have died or are fighting or are wounded or have left.”

“Plus, the remaining portion, some are in stress, some in economic stagnation, in poverty. And not everyone either wants, or can, or is ready to start a family now,” he said.

Soon after fighting broke out, Mother and Child, Ukraine’s largest fertility clinic, and other establishments started to offer steep discounts or free-of-charge service to military personnel and their families, including freezing sperm.

For the men, who make up the majority of Ukraine’s military, this offers the option to father children even if they are wounded or killed, Radko said.

Last year, Ukraine’s parliament passed a law providing for government support for such procedures, and servicemen can have their sperm preserved for three years after their death. About 200 members of Ukraine’s military come to Mother and Child every month. Some 3,000 servicemen have so far taken advantage of the service.

The decision to come to the clinic is clearly a difficult one — men and women are confronting the possibility of their death or raising a family alone, Radko said. Still, they come.

“The war was 95 percent part of our decision to try this sort of procedure,” said Yevhen, a soldier, who spoke on the condition that he be identified by only his first name. His wife is now in the fifth month of her pregnancy.

“I’m the only one in the family,” he said. “If I die somewhere, then my family line would be cut off and the meaning of life for my parents would be lost. It would be like there would be no one to live for. And I thought that even if it happens, that I have to give my life for our country, I would like to leave behind a piece of myself so that it lives.”

As desperate as the need is to improve the demographic situation, Ukraine’s approach differs sharply from that of Russia, which is experiencing its own drastic population decline. The Kremlin is urging women to forgo education and careers to prioritize child-rearing, while branding feminists, LGBTQ+ activists and others as purveyors of a “destructive ideology.”

In contrast, Ukraine has “respect for each individual’s personal right to choose how to live his or her life,” said Marchak, the deputy minister. “We do not want for a woman, who doesn’t want for different reasons to have kids, to feel guilty or uncomfortable.”

After the war, Ukraine will need to transition to a smaller, better educated country, with an emphasis on technology, defense industry and agriculture, said Timofiy Mylovanov, head of the Kyiv School of Economics.

This is achievable, he said. But Ukraine will also need to import a large number of foreign workers, and “migration will be an economic policy.” Otherwise, it will be “an aging and shrinking population,” where the elderly greatly outnumber the young.

But immigration by other groups could create “frictions,” he said. Ukraine’s 2001 census showed the population consisting of more than 95 percent of White, Slavic groups — largely Ukrainians and Russians — and little has changed.

“So now there’ll be a discussion within Ukraine,” Mylovanov said. “What’s the identity of Ukraine?”

At a recent Kyiv conference dedicated to Ukraine’s demographic strategy until 2040, discussions were heated, with some arguing that Ukraine needed to preserve its cultural and ethnic makeup.

Mylovanov said the threat from Russia meant just the opposite: Ukraine needed to accept large numbers of workers from abroad.

“We live next to a neighbor who wants to wipe us out. We need an army, if we want to exist — that means a lot of people,” he said.

Anastacia Galouchka contributed to this report.