The Science of Anti-Russian Propaganda

7 mins read

Propaganda as a Science

Sigmund Freud explored the irrationality of “group psychology” that overrides the rational and critical capacities of the individual. Freud recognised that “a group is extraordinarily credulous and open to influence, it has no critical faculty”.1 Conformity to the ideas of the group is powerful exactly because it is unconscious. Freud defined group psychology as being: “concerned with the individual man as a member of a race, of a nation, of a caste, of a profession, of an institution, or as a component part of a crowd of people”, which form a collective group consciousness, social instinct, herd instinct or tribal mentality.2

The nephew of Sigmund Freud, Edward Bernays, built on the work of his uncle to develop the foundational literature on political propaganda. Bernays aimed to manipulate the collective consciousness and identity of the group to control the hearts and minds of the masses without their awareness of being manipulated:

“The group has mental characteristics distinct from those of the individual, and is motivated by impulses and emotions which cannot be explained on the basis of what we know of individual psychology. So the question naturally arose: If we understand the mechanisms and motives of the group mind, is it not possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing it?”.3

Edward Bernays and Walter Lippman both worked in propaganda for the Woodrow Wilson administration. Bernays had assisted in convincing the American public to join the First World War by selling war as perpetual peace with slogans such as “the war to end all wars” and to “make the world safe for democracy”.

After the First World War, Bernays used his expertise to manipulate public opinion for commercial purposes with marketing campaigns. For example, Bernays led a marketing campaign convincing women it was feminine and emancipating to smoke cigarettes with the “Torches of Freedom” campaign. Bernays paid women to smoke in the Eastern Sunday Parade of 1929, which follows the principle of source credibility, as propaganda is more efficient when people trust the source and are unaware that it is propaganda.

Bernays used the same marketing principles for political aims as he was also hired by United Fruit Company when the government of Guatemala introduced new labour laws to protect workers. Bernays convinced the American public that liberal capitalist president of Guatemala was a communist who threatened basic freedoms. After Bernays shifted the American public opinion with deception, President Eisenhower launched a military intervention to topple the government under the auspices of fighting communism and defending freedom. In the 1920s, Joseph Goebbels, who would become the Nazi propaganda minister, became an ardent admirer of Bernays and emulated his propaganda techniques. As Bernays later acknowledged: “They were using my books as the basis for a destructive campaign against the Jews of Germany”.4

As the world became more complex, the general public became more reliant on cognitive shortcuts that often rely on assigned identities to process complex questions. People have to make hundreds or thousands of interpretations and decisions daily, and completely rational choices depend on an extensive assessment of alternatives and knowledge of relevant variables. Heuristics are manipulated by constructing stereotypes based on real or fictitious experiences and patterns of behaviour.

Most leading scholars on propaganda recognised that democracies are more likely to engage in propaganda as there is a greater need to manage the masses when sovereignty resides among the public. Propaganda is also assumed to be the instrument of state media. However, propaganda relies on source credibility as the message has greater influence when transmitted through a seemingly benign third party. American and British propaganda was more effective than Soviet propaganda during the Cold War as Western propaganda could be disseminated through private corporations and “non-governmental organisations”. Propaganda used to be considered a normal profession until the Germans gave it negative associations in the First World War. Edward Bernays renamed propaganda “public relations” to distinguish between “our” good propaganda and “their” malicious propaganda.

Anti-Russian Propaganda: The Virtuous “Us” Versus the Evil “Other”

Human beings organise in groups such as families, tribes, nations or civilisations for meaning, security and even a sense of immortality by reproducing the group. Conformity to the group is driven by powerful instincts to organise around common beliefs, ideas and morality, while the group also punish the individual for failing to conform. Group conformity is a survival instinct that strengthens when confronted by the out-group. The “Othering” of a people or state is instrumental in exaggerating the perceived homogeneity of the in-group and strengthening the collective identity and solidarity, while the out-group is depicted and de-legitimised as the diametrically opposite. Stereotypes are used to mask reason and reality, such as the humanity of the adversary. Propaganda entails appealing to the best in human nature to convince the audience to do the worst in human nature.

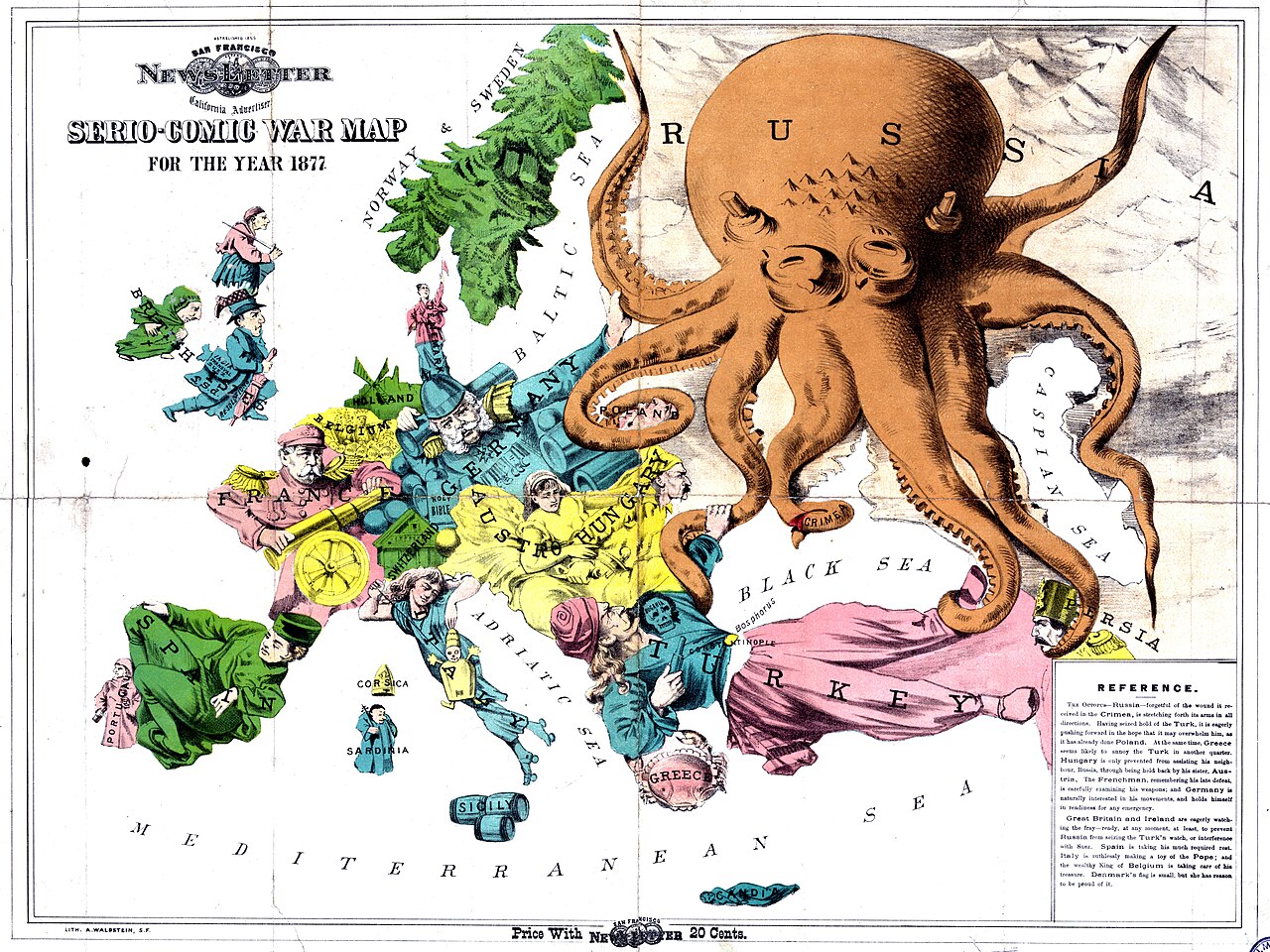

Russia has for centuries been depicted as the civilizational “Other” to the West. The West and Russia have been juxtaposed as Western versus Eastern, European versus Asiatic, civilized versus barbaric, modern versus backward, liberal versus autocratic, and even good versus evil. During the Cold War, ideological dividing lines fell naturally by casting the debate as capitalism versus communism, democracy versus totalitarianism, and Christianity versus atheism. After the Cold War, anti-Russian propaganda was revived by interpreting all political questions through the simplistic binary stereotype of democracy versus authoritarianism, which provides little if any heuristic value to understand the complexities of relations. Portraying Russia as a barbaric other suggests that the West must civilise, contain or destroy Russia to enhance security. Furthermore, a civilising mission or socialising role of the West infers that dominance and hostility are benign and charitable which reaffirms West’s positive self-identification. All competing power interests are concealed in the benign language of liberalism, democracy and human rights.

Russophobia is not a transitory phenomenon but has proven itself to be incredibly enduring due to its geopolitical function. Unlike the transitory Germanophobia or Francophobia that have been linked to particular wars, Russophobia has an endurance comparable to anti-Semitism. From the efforts of Peter the Great to Europeanise Russia in the early 18th century to the similar efforts of Yeltsin to “return to Europe” in the 1990s, Russia has not been able to escape the role of the “Other”. The West’s rejection of an inclusive European security architecture after the Cold War, in favour of creating a new Europe without Russia, was largely legitimised by the supposed lasting dichotomy between the West and Russia.

Walter Lippman observed more than a century ago that propaganda is good for war but bad for peace. Propaganda strengthens internal solidarity and assists with mobilising resources against an adversary. However, the public will reject a workable peace if they believe there is a struggle between good and evil. Lippman argued that to overcome the public’s inertia towards conflict “the enemy had to be portrayed as evil incarnate, as absolute and congenital wickedness… As a result of this impassioned nonsense, public opinion became so envenomed that the people would not countenance a workable peace”.5

This lesson remains true today. Selling the narrative of an evil and imperialist Russia unleashing an unprovoked attack on a thriving democracy justified fuelling a proxy war and rejecting any negotiations. The Hitler analogy is powerful as peace requires victory, while diplomacy is appeasement. A workable peace is now difficult to justify as it entails that good compromise with evil.

The article includes excerpts from my book “Russophobia: Propaganda in International Politics”

- Freud, S., 1921. Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego [Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse], Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, Vienna, p.13. ↩︎

- Freud, S., 1921. Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego [Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse], Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag, Vienna, p.7. ↩︎

- Bernays, E., 1928. Propaganda. Liveright, New York, p.47. ↩︎

- Bernays, E., 1965. Biography of an Idea: Memoirs of Public Relations Counsel. Simon and Schuster, New York, p.652. ↩︎

- Lippman, W., 1955. The Public Philosophy. Little, Brown & Co., Boston, p.21. ↩︎