2 mins read

Open Appeal to Presidents Trump and Putin

We kindly invite you to review and sign the Open Appeal to President of the United States Donald Trump and President of Russia Vladimir Putin

12 mins read

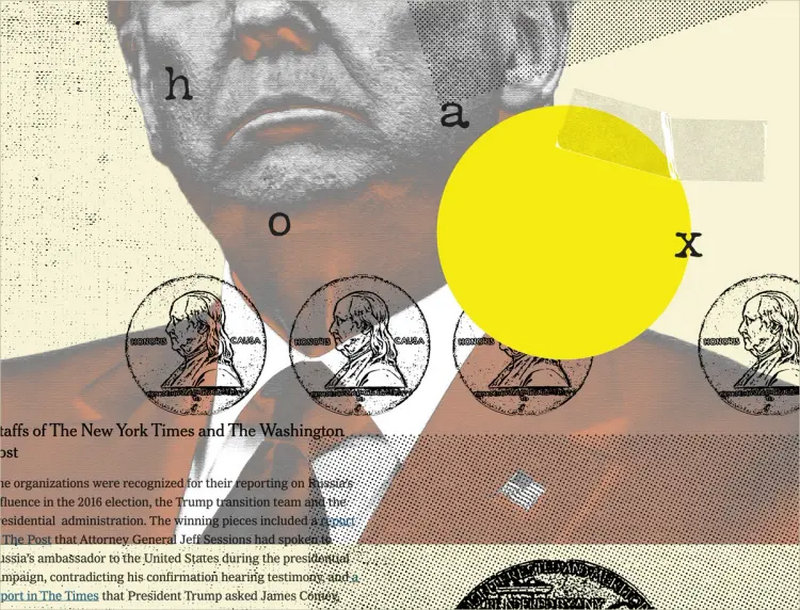

In the two years since it was filed, the defamation lawsuit has gone from a curiosity to a source of real concern in some of the country’s top newsrooms. On Sept. 30, 2021, President Donald Trump wrote to the Pulitzer Prize Board with an unusual demand. The former president asked the board to “strip” the 2018 national reporting prize from the Washington Post and New York Times, which had been honored for their “relentlessly reported coverage” of “Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and its connections to the Trump campaign, the President-elect’s transition team and his eventual administration,” according to the citation at the time of the award.

The then-former president added in black Sharpie under his signature: “P.S. Our country has been hurt so badly by this criminal scam. Please do the right thing.”

It wasn’t the first complaint about that award. In 2019, the Pulitzer board, a volunteer body of 20 of America’s best-regarded journalists, had quietly commissioned a review of the coverage, which concluded the reporting was fine. But the stakes felt higher this time.

“Because of his standing in America and the likelihood of this could turn to litigation, we thought we should, with an open mind, look at it all again,” a board member, the veteran AP editor John Daniszewski, later said, according to the transcript of his deposition.

The board launched a second review whose author and substance, like the first one, remain confidential. But it, likewise, found no flaws in reporting which preceded and then covered Robert Mueller’s investigation of those subjects, stories on subjects like Trump aide Michael Flynn’s conversation with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak about sanctions, and Donald Trump, Jr.’s meeting with a Russian lawyer who claimed to have dirt on Hillary Clinton.

In November 2021, the board drafted a statement responding to Trump, according to Katherine Boo, the board member and investigative journalist who, with Daniszewski, took the lead on the project. (Daniszewski, Boo, and other board members declined to speak about the lawsuit, and their views and correspondence are drawn from depositions.) They sent the draft to the lawyers for Columbia University, which houses but does not run the Pulitzers, and then waited.

On May 31, 2022, Daniszewski sent then-Columbia President Lee Bollinger an impatient email: “We have a statement we wish to release, saying we have investigated his grievance thoroughly and we are denying his request to rescind the prizes,” he wrote. “We have held off with our answer because the counsel for Columbia wanted to review it. But we have not heard from them in some time despite repeated inquiries.”

Finally, on July 18, the Pulitzer Board released its statement: “The separate reviews converged in their conclusions: that no passages or headlines, contentions or assertions in any of the winning submissions were discredited by facts that emerged subsequent to the conferral of the prizes.” they wrote. “The 2018 Pulitzer Prizes in National Reporting stand.”

That statement is now the cause of action for the strangest and most interesting piece of litigation in President Donald Trump’s effort to literally relitigate the journalism of the last decade. And to be clear, I am not re-reporting or resuscitating any of the claims against Trump or his 2016 campaign here: I am reporting on this lawsuit that he filed, identifying himself as President Trump, which raises the issue of whether views that were, arguably and in the views of many, reasonable in 2018 could be found to be defamatory in 2022.

The December 2022 lawsuit, which pleads “defamation by implication” among other claims, is nominally directed at the 20 board members. They include leading figures in American journalism: New Yorker editor David Remnick, Boston Globe editor Nancy Barnes, the former Los Angeles Times editor Kevin Merida, The Atlantic’s Anne Appelbaum, the New York Times’s Gail Collins and Carlos Lozada, as well as the poet Elizabeth Alexander and the novelist Viet Than Nguyen. (Semafor executive editor Gina Chua currently sits on the board, but joined after the events in question and is not involved in the suit.)

The suit takes advantage of what lawyers allied with Trump and independent media lawyers alike say was a major error by the Pulitzer Board. Publishing a new statement, with reference to new, anonymous reporting, gave Trump a cause of action within the statute of limitations that would otherwise have protected both the underlying reporting and the prize. The Pulitzer Board, eschewing the transparency its members usually advocate, is fighting in court to keep the names of the reviewers and content of the review secret. A spokesperson also declined to say who is paying for the defense, though two people involved said Columbia is covering the costs.) The case has been moving at a leisurely pace over Zoom calls with Judge Pegg, a senior judge and the third assigned to the case, which was filed in Okeechobee, Florida, between Tampa and Miami.

But the real target of the lawsuit (written in a particularly high Trump Style) appears at times to be less the defendants, or any particular factual claim, and more the theme or gist of the coverage. The word “narrative” appears 11 times in the original filing. (A sample from paragraph 46: “The lies were so maliciously fabricated to the point that many actually believed the disgustingly fake narrative that President Trump was a Russian asset.”)

The suit targets the center of the long war between Trump and much of the media, the heated Russia investigation that consumed the first years of his first term. The defendants are currently appealing the judge’s denial of their motion to dismiss the case — they argue that the 19 defendants with no particular connection to Florida should be struck, and that the statement was merely opinion that can’t be the basis of a defamation claim. Trump’s filing, meanwhile, has the curious feature that it doesn’t cite any particular factual errors, and argues instead that defamation emerges from “the theme established by and pervading the Awarded Articles is that the now irrefutably debunked Russia Collusion Hoax was, in fact, real.”

The suit also argues that it is “ultimately immaterial” whether the Times and Post journalists were in on what Trump sees as a plot against him. What matters instead, Trump argues, is that the board affirmed the prize “particularly when many of the key assertions and premises of the Russia Collusion Hoax that permeated the Awarded Articles had been revealed by the Mueller Report and congressional investigations as false after the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in National Reporting had been awarded.”

The Pulitzer lawsuit is worth considering because, behind the bluster about hoaxes and the arguments about whether an obscure Florida court is the right arbiter for this issue, it reveals two questions that neither Trump nor the media have been eager to address.

First, in my trade, journalism, we have a formula that corrects errors of fact, no matter how minor — but no real mechanism for correction when we get the whole gist of the story wrong, as of course regularly happens when you’re a reporter on deadline with the first draft of inscrutable, too-soon-to-tell history.

The pursuit of tantalizing hints of collusion between Trump’s campaign and Russia was, in my view, honest and legitimate, and I edited stories on that hunt when I was leading BuzzFeed News — breaking factual news about a Russian approach to Carter Page, about Trump’s Moscow real estate aspirations, and about a certain unverified — but widely circulated — dossier. It’s also worth noting that the stories in the Pulitzer package reported accurately and with caveats on contact between Trump aides and Russian officials. One key Times story, in February 2017 for instance, reported on an investigation of “whether the Trump campaign was colluding with the Russians” and said that “officials interviewed in recent weeks said that, so far, they had seen no evidence of such cooperation.”

And yet: Journalists who covered the story should acknowledge that this high-stakes line of reporting, with its breathless cable news and social media cheerleading, did not seriously bear out. The Mueller report concluded that investigators “did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.”

And in retrospect, some of that reporting (like similar reporting after the 2016 election on Facebook) was powered by a delusion: That Trump’s election must be the result of some trick, and wasn’t otherwise possible. That reaction to losing an election is a particularly ugly feature of contemporary politics, and worth disclaiming.

The journalistic pursuit of alleged collusion was not, in my view, a “hoax.” But it was, perhaps, something a little like this month’s drone hunt in New Jersey, which Washington figures have variously, confidently declared the spawn of an Iranian “mothership” and an obvious Chinese plot. Take some curious observable facts and real adversaries, add some whispers from Washington national security figures and statements from members of Congress, and journalists eager to feed a hungry audience, and you can produce a proper mass delusion.

You don’t need to go around revoking prizes for solid reporting in real time to consider the central question that Trump’s lawsuit asks: Even if it was reasonable for us in 2017 to chase the connections between Trump and Putin, and even if that reporting was accurate in its details, was it still reasonable to celebrate that reporting today?

***

Trump’s case, meanwhile, contains its own tacit concession. “The Russia Hoax” has quietly become “The Russia Collusion Hoax.” This an unstated acknowledgement of Robert Mueller’s other conclusion, that “The Russian government interfered in the 2016 presidential election in sweeping and systematic fashion.” That included the stunning Wikileaks operation, as well as the Internet Research Agency’s social media mischief. And it’s no longer in dispute — embarrassing as it is those it was intended by the Russians to benefit.

Trump and his supporters sought, for a time, to conflate those facts with the shaky collusion allegations, and to dismiss them. The lawsuit filed by President Trump, helpfully, separates them again.

Three lawyers deeply familiar with the case whom I spoke to — two sympathetic to the defendants and one to Trump — said they believed the Pulitzer Board had blundered badly in issuing its statement. Had it simply stayed silent, or simply offered its opinion that the 2018 prize was sound, the stories and the prize would have remained safely outside the statute of limitations for defamation. The statement, Trump now argues, gives him a target because it isn’t just opinion — it’s disclosing and relying on new, anonymous and opaque reportage, in the form of the board’s review.

“This lawsuit is about intimidation of the press and those who support it—and we will not be intimidated,” the board said in a statement through a spokesperson.

Trump’s top legal adviser, Boris Epshteyn, declined to comment on the case, but Trump spokesman Steven Cheung said the president-elect is “committed to holding those who traffic in deception and fake news accountable” and that “we look forward to seeing this case through to a just conclusion.”