by Lyle J. Goldstein of the Naval War College via Many observers of President Vladimir Putin’s 2021 “State of the Nation” speech have focused on his statements with regards to “red lines,” since he let it be known that Russia’s […]

by Lyle J. Goldstein of the Naval War College via

Many observers of President Vladimir Putin’s 2021 “State of the Nation” speech have focused on his statements with regards to “red lines,” since he let it be known that Russia’s answer would be “asymmetric, rapid, and tough.” Such a comment is not unexpected, but his next statement has thrown Western observers into quite a tizzy. He said he hoped that nobody would cross these red lines, but then declared, “We will determine ourselves [Putin’s emphasis] where these red lines are according to the circumstances of each situation.” And there are many such situations now – that’s for sure.

Never mind that national security issues represented a mere 10% of Putin’s one hour and 15 minutes address. The Russian leader spent most of his time focused on the Covid-19 response, reviving the economy, infrastructure, education, and particularly on assistance for overburdened Russian moms. Still, the headlines in all the major Western newspapers led with the new allegedly menacing rhetoric from Putin. The statement is admittedly troubling, and even perhaps befuddling. Such is often the case with a “riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside of an enigma.”

The point of a “red line” after all, at least according to conventional strategic logic, is that it is red. Ideally, the red is a very bright shade and we may even hope that it is actually flashing red – the better to prevent a miscalculation. Such lines are meant to clarify the boundaries between peace and war. The clearer the line, the more stable a given militarized crisis situation will be, since both sides understand the boundaries and related risks. Since the dawn of the nuclear era, one might say, that such red lines have assumed even epochal importance. Consider the most dangerous moment of the Cold War, the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, in which it became obvious to all that Moscow had rather clumsily transgressed Washington’s red line by stationing nuclear weapons in Cuba.

More recently, the concept of a red line in American political discourse has become a cudgel to beat up on the foreign policy legacy of President Barack Obama. In this case, the former President stands accused of undermining U.S. credibility by failing to use force after asserting that the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons constituted a red line. That amounts to an unfair accusation, not least because the U.S. had no good options in Syria, but hopefully all sides in the U.S. foreign policy elite, including even the President himself, got a lesson in casually throwing around words like “red line.”

A more sobering consideration, however, is that a discussion about a red line with Syria is obviously different than one that entertains the concept of a red line with respect to nuclear-armed powers. Some have pondered: where is the red line with North Korea? How many would die if one side or the other lurched over that line, even if by accident or due to misperception? Yet, when it comes to fully bulked up nuclear powers like China and particularly Russia, the issue is absolutely grave, since we are talking about countries that can “end” the U.S., perhaps in a matter of hours, even if we have the solace that we would take our adversary down in flames with us.

Yet, Putin’s comment on red lines does not simply underline the serious nature of contemplating war and peace between the U.S. and Russia. Americans should ask the uncomfortable question: why do the U.S. and its allies appear to be encroaching upon so many different Russian red lines in so many “situations” simultaneously? Indeed, Russian interests are now directly engaged against U.S. interests, or those of our allies, in a zero-sum pattern on a vast front stretching from the Arctic, to the Baltic, through Belarus to the Donbass and Crimea, and all the way down to the Caucasus and beyond.

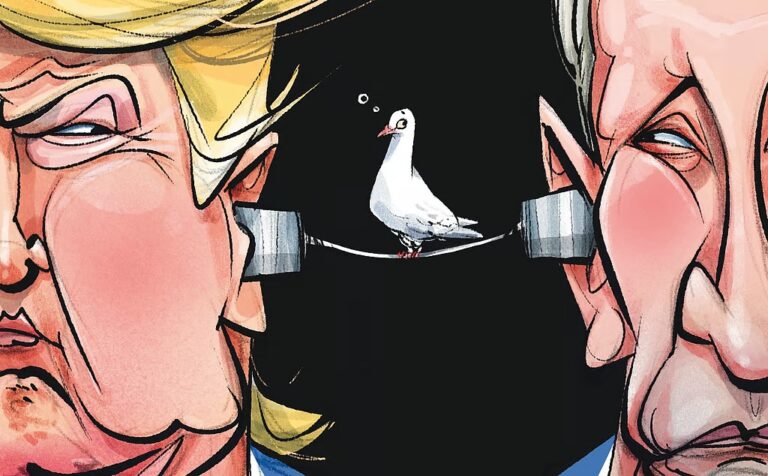

A common sense notion of peace, and indeed survival, for the 21st century must incorporate limits and crucially the principles of realism and restraint. We should not be touching the red lines of other major, nuclear armed powers on a daily basis. The fact that Western strategists seek to probe Russia’s red lines in Eastern Europe is itself a powerful indictment of U.S. foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Wiser voices, such as George Kennan, counseled against such hubris and we never should have reached this sad point in our dealings with the Kremlin.

We must learn to live amicably with Russia or risk a continuing succession of showdowns on the pattern of the Cuban Missile Crisis– this time on Russia’s door step, with a Kremlin that has an infinitely more capable nuclear arsenal when compared to the early 1960s. In that unfortunate case, we may again be taught some lessons about red lines.