Sanctions would undermine climate diplomacy. By Stephen G. Gross via In March, the Biden administration announced it was considering sanctions on companies involved in the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—even mulling a special diplomatic envoy to navigate the […]

Sanctions would undermine climate diplomacy.

By Stephen G. Gross via

In March, the Biden administration announced it was considering sanctions on companies involved in the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—even mulling a special diplomatic envoy to navigate the tangled geopolitics it has generated. Now, the White House is facing mounting pressure from Congress to follow through with a full diplomatic push.

Nord Stream 2—which is slated for completion this year—will double the existing flow of natural gas from northern Russia to Greifswald, Germany. Advocates of the pipeline herald it as a step toward European energy stability while critics pan it as a scheme by politicians in the pocket of energy conglomerates. Others, like U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, condemn Nord Stream 2 as a “Russian geopolitical project intended to divide Europe and weaken European energy security.”

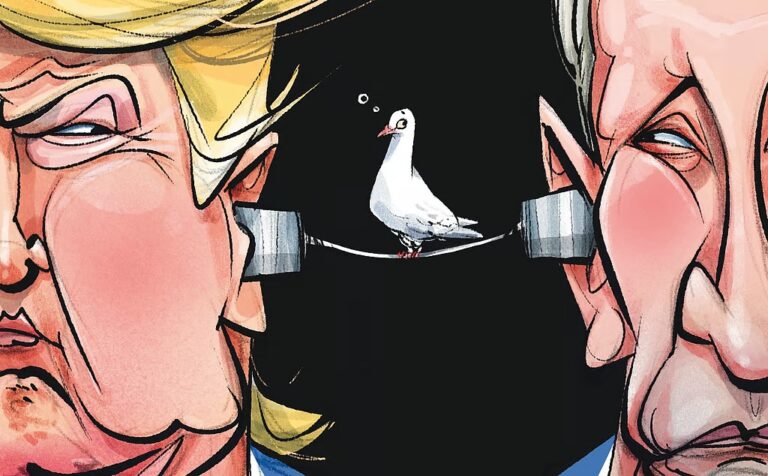

There are many reasons to see Russia and President Vladimir Putin as agents of geopolitical destabilization. But natural gas is not one of them. In fact, sanctioning Germany over Nord Stream 2 would damage transatlantic relations and undermine the very sort of cooperative diplomacy Europe and the United States need to fight climate change. As Germany moves closer toward a carbon-friendly grid, Russian natural gas is—at best—a temporary bridge on the path to full reliance on renewables. That’s especially true considering the European Union is now hoping to abandon natural gas by 2050 in an effort to go carbon neutral. Instead of sanctions on Nord Stream 2, U.S. President Joe Biden should help Europe green its electricity system so it can reach a clean energy future on schedule. For those concerned about geopolitics, such an approach has the added benefit of making Russian natural gas redundant.

Absent from the U.S. discussion on Nord Stream 2 is any effort to understand Germany’s perspective on natural gas. Indeed, Germany’s pipeline politics only makes sense against the backdrop of the country’s energy transformation or “Energiewende.” Since 2000, Germany has been working to place its electricity sector on a solar, wind, and biogas foundation—a process that was hastened by the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011. The country has made great progress. But the government has financed renewables with heavy surcharges, taxes, and grid fees, giving Germans some of the highest electricity prices in the world.

In addition to being costly, renewable power is also intermittent. Running the grid requires a stable base load of electricity for when the wind does not blow and the sun does not shine. Since German Chancellor Angela Merkel began to phase out atomic power in June 2011, Germany has covered much of its base load with lignite coal, a dirty form of energy that is terrible for the atmosphere. But in 2020, Berlin made the commendable but highly contested decision to phase out coal-powered electricity entirely by 2038. Environmentalists say this is not soon enough. But for a nation with thousands of coal jobs in economically stagnant regions, Merkel’s is an impressive promise—strikingly different from other coal-producing nations like the United States, Poland, and China, which have hardly considered such a far-reaching policy.

Natural gas has become a way to enable Germany’s coal and nuclear phaseout.

With nuclear- and coal-powered generation slated for termination, how can Germany cover its base-load electricity? Batteries are one answer; investment in storage is growing, and the technology is improving dramatically. But covering the electricity needs of a wealthy, industrial nation through wind and solar plus storage will take time, investment, and state action. As a result, natural gas has become a crucial but hidden pillar of the Energiewende—a way to enable Germany’s coal and nuclear phaseout. Since 2000, the country’s power production from natural gas has nearly doubled; as a source of electricity, only renewables have grown faster.

Now, the United States is asking Germany to stop a natural gas project at the very moment it is needed more than ever. Washington is less concerned about the climate implications of Nord Stream 2 than the pipeline’s feared political and economic repercussions. Instead of working with Russia, Washington wants Germany to buy liquified natural gas (LNG) produced from the United States. But according to most estimates, U.S. LNG is more expensive than Russian pipeline gas. LNG also has a notoriously volatile price.

In calling for the end of Nord Stream 2, Blinken is creating headwind for Germany’s climate policy—and asking German consumers to pay even higher prices for their power. Added to Germany’s bill would likely be expensive lawsuits if the remaining 93 miles of the pipeline were never completed, as companies like Gazprom and Royal Dutch Shell try to recoup sunk investments worth billions of dollars. The whole ordeal, moreover, is out of sync with Biden’s pledge to work with all countries—including adversaries—to combat climate change.